Introduction

“Picturing Mobility: Photographs of Black Tourism and Leisure during the Jim Crow Era” is a narrative-based research project and part of the Interdisciplinary CoLab Internship at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Our website originates from Dr. Elizabeth Patton’s archival research for her book, “Representation as a Form of Resistance: Documenting African American Spaces of Leisure during the Jim Crow Era,” which examines the history of Black leisure and tourism in the U.S., –with a lens on marketing, advertising vernacular photography, and home movies– to investigate current forms of travel/leisure-based racism and how it affects Black tourism. This virtual exhibition acts as an introduction to the exhibition that will be held in UMBC’s Albin O. Kuhn Library Gallery in the fall of 2025, which implores viewers to consider what it meant to be a Black American during the Jim Crow era, specifically in the context of leisure activities. Archival research was conducted using sources primarily from the Morgan State University Special Collection, Maryland State Archives, DigDC, The Burns Collection & Archive, and The Peter J. Cohen Archive in New York. This website focuses on popular Black leisure activities and destinations in the mid-Atlantic region from 1876 to 1968.

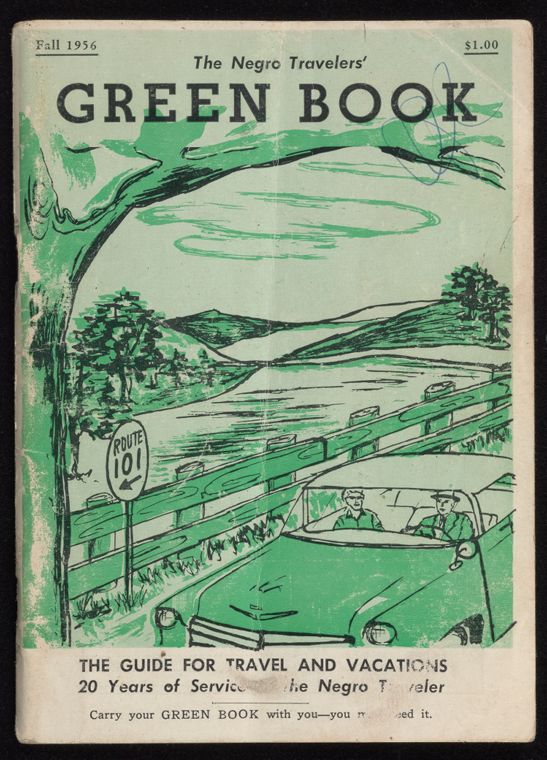

The Jim Crow Era was one of the most racially tense periods in American history, as it was a period of mandated racial segregation that spanned from the Reconstruction Era until its end in the 1960s. At this time, Black folks’ and their daily lives were dictated by segregation from laws (de jure) and community customs (de facto). As a result of living under deference and the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision, which legalized state-mandated segregation laws, segregation was quickly ingrained into the American psyche. Subsequently, the “separate but equal” mindset cemented itself as the norm, as most public spaces, such as parks, restaurants, schools, and hotels were racially segregated. Segregation was more than physical separation, it was a way to diminish the freedom and dignity of Black individuals while upholding white supremacy. As a consequence of racial tension, traveling was often humiliating and dangerous for Black families and individuals, with aspects like sundown towns impacting travel and leisure habits. Most trips were carefully planned out far in advance, and specialized travel guides, such as The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, were created to aid Black individuals through their travels by highlighting safe, popular leisure spots.

This exhibition also acts as a counternarrative—a narrative that details the experiences of those who are historically excluded or oppressed—challenging the dominant understanding of Black history and culture during the era. The photographs included in this virtual exhibition are testaments to a story that isn’t often told during this time period, a story of Black joy and leisure. The idea of using photography to share a different, underrepresented perspective was not uncommon. W.E.B. Du Bois, a Black sociologist, and civil rights activist, used studio portrait photographs of upper-middle-class African Americans in his display at the 1900 World Fair Exhibition in Paris to demonstrate that Black people were innovative, cultured, and intelligent, which countered the popular narrative that Black people were uneducated and unable to form community. Our exhibition focuses on people documenting moments of their personal lives, as opposed to posed, professional studio portraits. It is important to recognize that throughout most of the Jim Crow period up until the 1950s, having access to a portable camera was uncommon and such ownership was reserved for upper and middle-class African Americans. Additionally, many camera companies did not advertise to Black people, which worked to further limit the narrative surrounding the Black experience. Photography for many African Americans was used as a tool to communicate to their families and community, a counternarrative that had been purposefully excluded by challenging common perceptions of Black life during the Jim Crow era. Subsequently, these photographs work to humanize Black people and their experiences.

The Ethics of Interpreting Snapshots

While exploring this virtual experience, we encourage viewers to approach these photos from a personal perspective, instead of a purely historical analysis. While the historical context is important to understand the inherent value of these photographs, it is imperative to appreciate the emotional aspect just as much. We urge viewers to think about how the photos make them feel. Moreover, we want to recognize that some of the connections and claims we make throughout this exhibit are speculation, as we don’t have all the answers surrounding the content and context of these photographs. This is something that we are aware of and appreciate. Lastly, we want to recognize the ethical responsibilities we have while dealing with private materials like these photographs, we took a lot of care to ensure the balance of privacy and public interest while creating this digital exhibition, in order to highlight the importance of context and avoid the risk of misinformation.

Featured Image

- Addison Scurlock, Picnic, Highland Beach, Maryland, c. 1931, printed 1982. Gelatin silver print. The Photography Collections, University of Maryland, Baltimore County (P82-17-014)