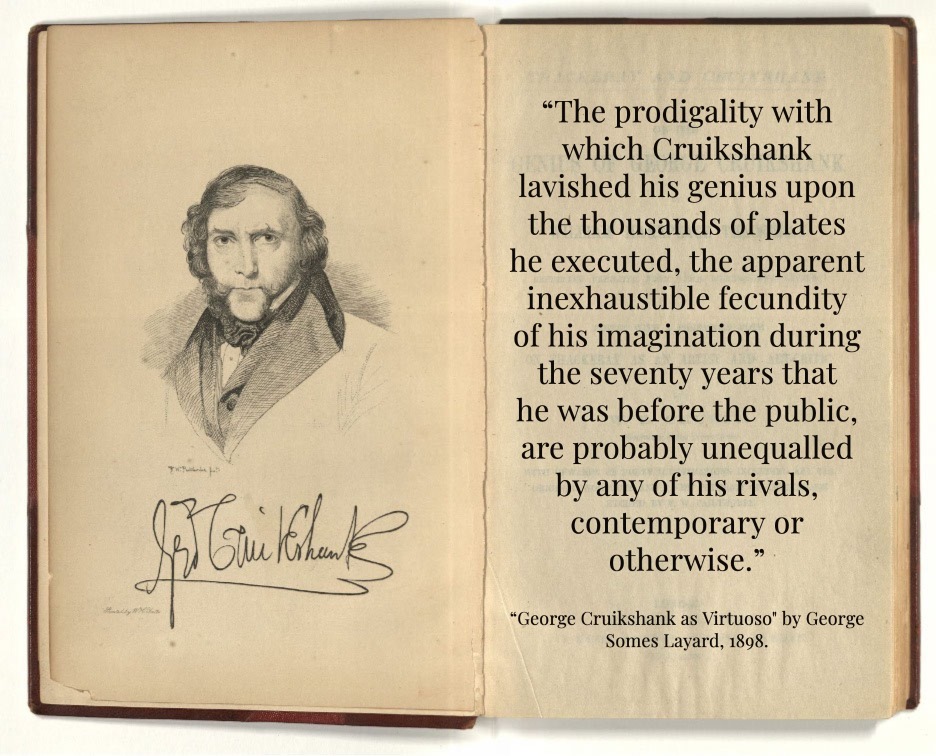

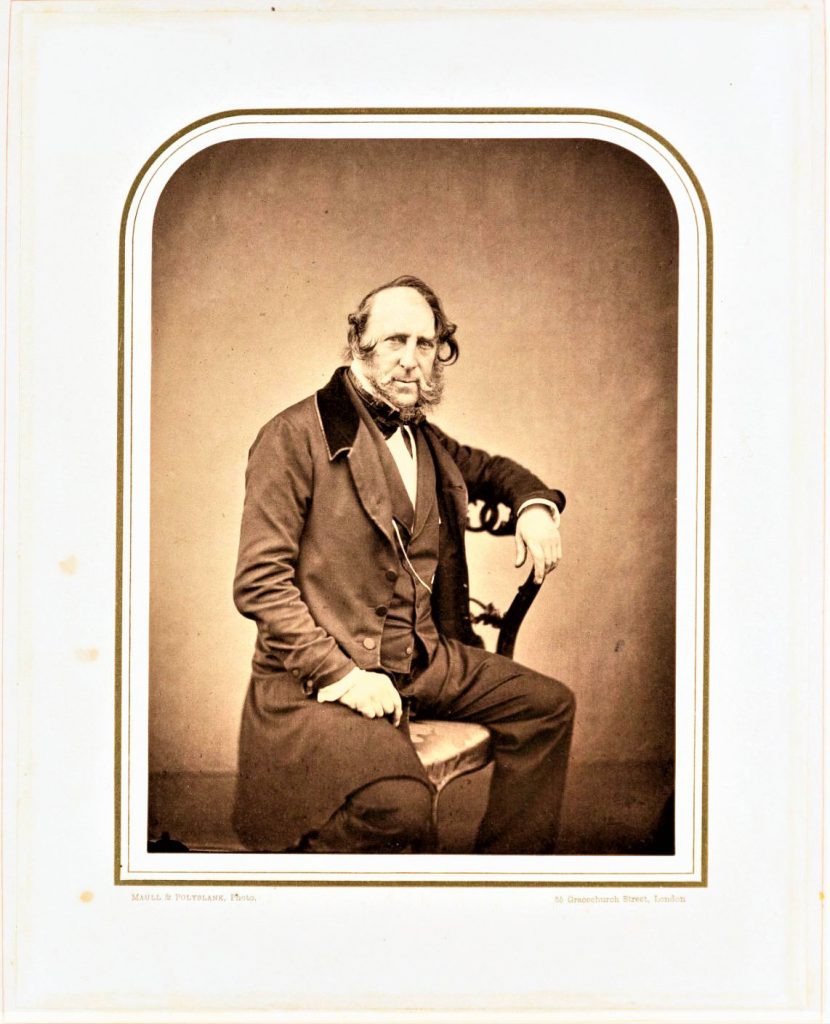

Biography & Portraits

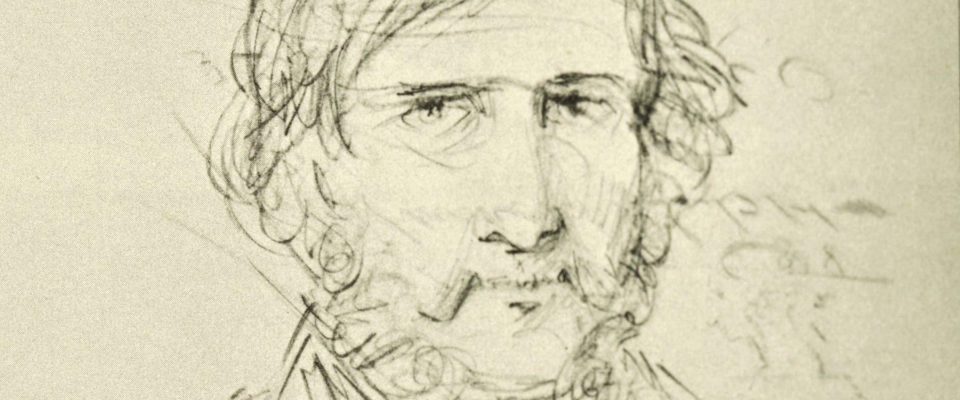

George Cruikshank (1792-1878) was destined to be an engraver. Like his father, Isaac, and his older brother, Isaac Robert, George spend his days scratching away on wood, steel and copper. But unlike the other Cruikshanks, George would become a household name, the “modern Hogarth” or, simply, “The Great George.”

Cruikshank’s career spanned the Regency, Georgian and Victorian eras in London, England. He began his career as a caricaturist and printmaker and later became known for his stunning book illustrations and temperance work. Cruikshank may be best known for his collaboration with Charles Dickens, especially for his work on Oliver Twist. He produced over 2,000 individual prints, tens of thousands of sketches and cuts, designs, plates and placards and illustrated over 860 books. His creations as well as personal correspondence are held in collections around the world.

Despite this vast body of work, Cruikshank never received formal accolades or substantial financial compensation. Living sketch-to-sketch, Cruikshank eventually received a small pension from the Royal Academy to which he was never elected. By some measures, Cruikshank was a failure and by others a phenom.

George was born September 27, 1792 to Isaac and Mary Cruikshank. Father Isaac Cruikshank was a well-known caricaturist during the 1790’s and both his sons Isaac Robert (known as Robert) and George went into the family business.

“When I was a mere boy, my dear father kindly allowed me to play at etching on some of his copper plates–little bits of shadows, or little futures in the background–and to assist him a little as I grew older; and he used to assist me in putting in hands and faces”

Letter to Bibliographer G.W. Reid, quoted in Hamilton, Memoir of George Cruikshank, 1878

Yet, Cruikshank became a caricaturist somewhat by chance. Between 1790-1810, two British caricaturists were considered foremost in the field: James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson. By 1810, Gillray was no longer able to produce work as a result of his alcoholism, and though his father Isaac would have been the rightful successor of Gillray, Isaac’s death made George the heir apparent to the caricaturist’s throne.

At the beginning of his career, Cruikshank collaborated with political pamphleteers including William Hone, with whom he published, among other polemics, The Queen’s matrimonial ladder (1820), one of the pieces showing support for the beleaguered Queen Charlotte of England. Despite the less than spectacular professional response and poor compensation, George Cruikshank’s illustrations and caricatures held sway over public opinion, so much so that in 1820 King George IV paid him not to create his scathing caricatures of the sovereign.

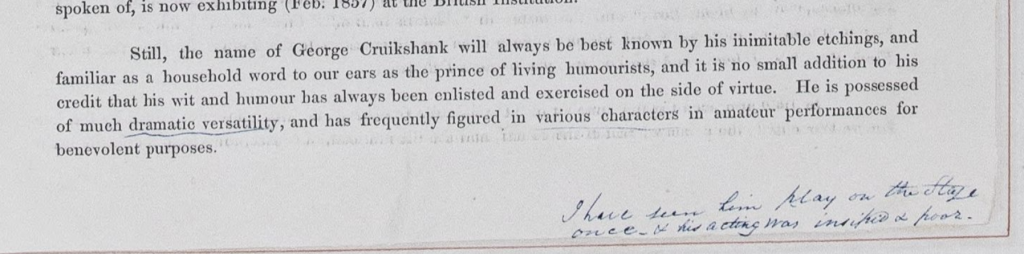

Whether telling tales and singing a popular ballads at the local pub, or in his later years, lecturing on the evils of alcohol, Cruikshank was known to “indulge in exaggerated gestures and theatrical pronouncements,” according to Robert L. Patten, his biographer. Indeed, he considered a life on the stage and many recognized that his acting experience informed his turn to dramatic book illustrations, though there were decidedly mixed reviews as to his acting talent.

The marginalia reads, “I have seen him play on the stage once-& his acting was insipid & poor.” Scraps and Sketches, 1828. Browse the full volume here.

In collaboration with his brother Robert, George published Adventures of Tom and Jerry in 1821, marking his turn towards book illustration. The success of their collaboration put the name Cruikshank into prominence. For the next decade, Cruikshank produced pieces for other acclaimed books including the first English translation of the Grimms Fairy Tales in 1823. By 1835, Cruikshank became known as the most important influential book illustrator in England. Around this time Richard Bentley, the publisher of the journal Bentley’s Miscellany made an offer to Cruikshank to illustrate Charles Dickens‘s Oliver Twist, and in 1837 the first chapter of Dickens’ famous work was published, solidifying both Dickens and Cruikshank as household names, at least for the time.

Both George and his brother Robert were heavy drinkers and George watched both succumb to complications from alcoholism. George, whose evenings after a long day in his studio would be spent in a tavern telling tales and sharing songs, would renounce alcohol in his later years, becoming a teetotaler.

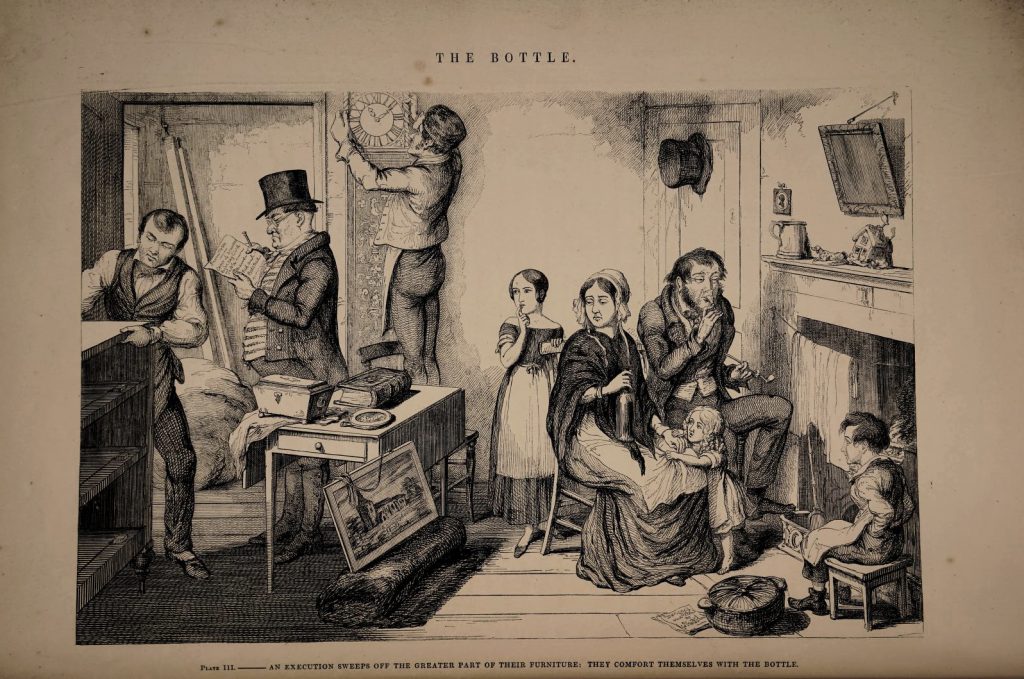

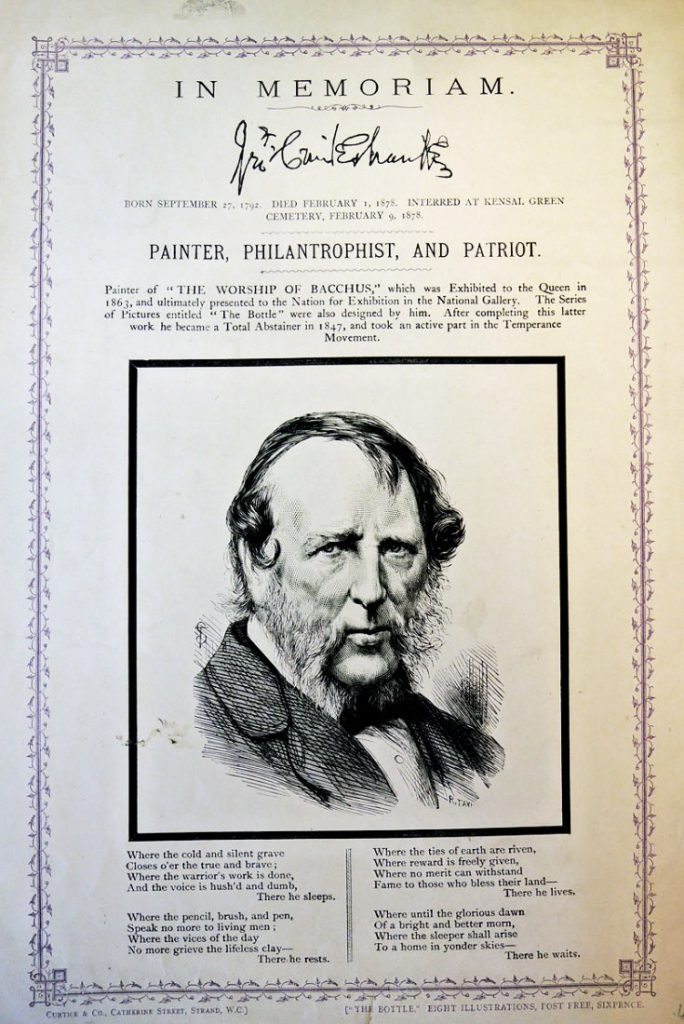

In 1847, commissioned to illustrate The Bottle, a series of etchings which showed the devastating effects of alcoholism on the individual and his family, Cruikshank stopped drinking and joined the Temperance Movement. Over the next 30 years he lectured on the dangers of alcoholism throughout England and while he still etched and sketched, his name and fame waned.

In many ways George Cruikshank was a living contradiction. Married twice (first to Mary Ann Walker in 1827 and then to Eliza Widdison in 1851), he did not have legitimate heirs, yet bore 11 children with his mistress, Adelaide Attree, a former servant, who lived nearby. He was often cruelly prejudicial in his depictions of people and at times harshly critical of Britain’s powerful elite. He was known to be good natured and to hold bitter grudges. Perhaps Robert Patten articulates Cruikshank’s enigmatic figure best:

“The real biography of any artist is contained not in the letters or the anecdotes or the diaries, but in the art. Cruikshank’s claim to importance rests less on his friendships (legion) and eccentricities (memorable) than on the pictures that poured from his studio daily for more than seventy years.”

Click on the images below for a closer look

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery