Political Satire

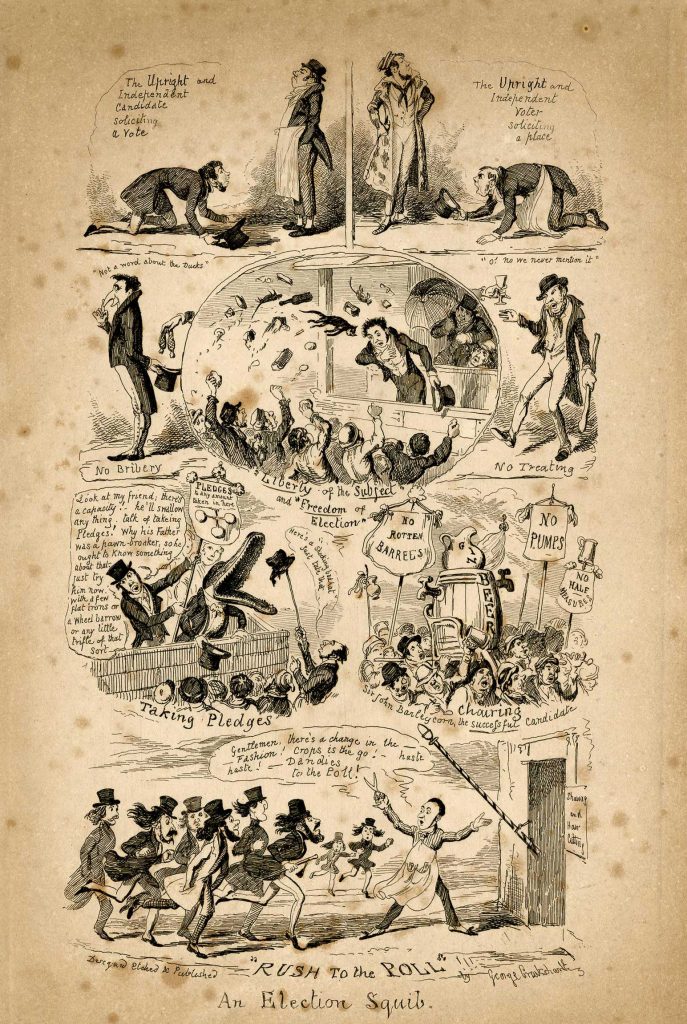

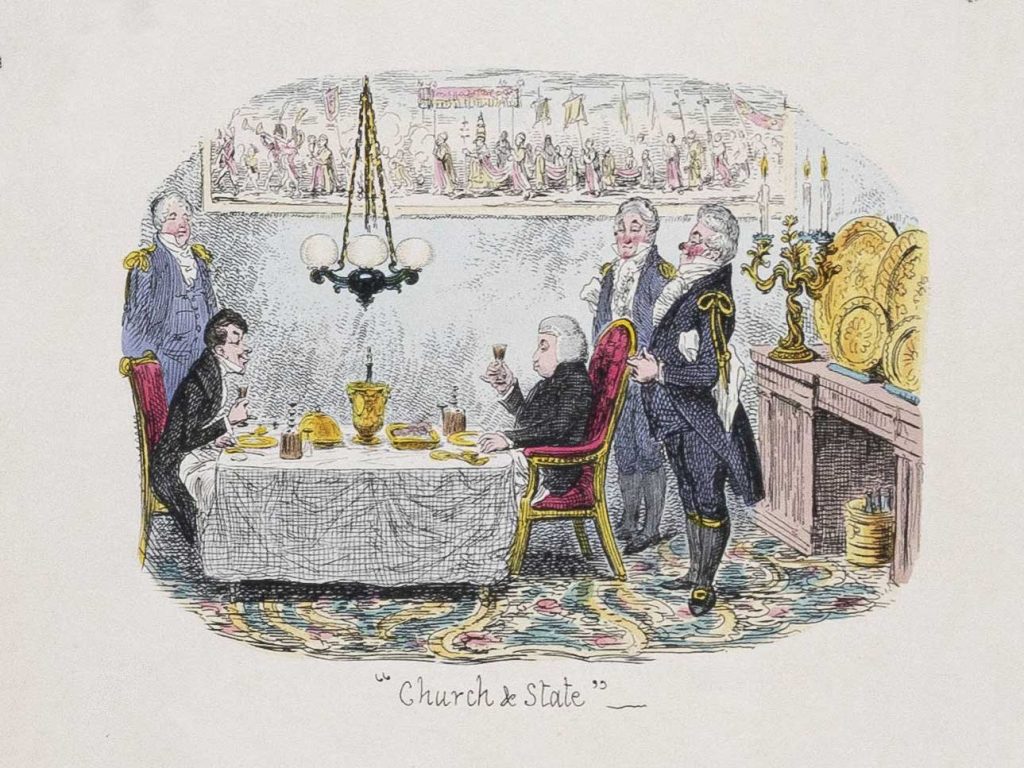

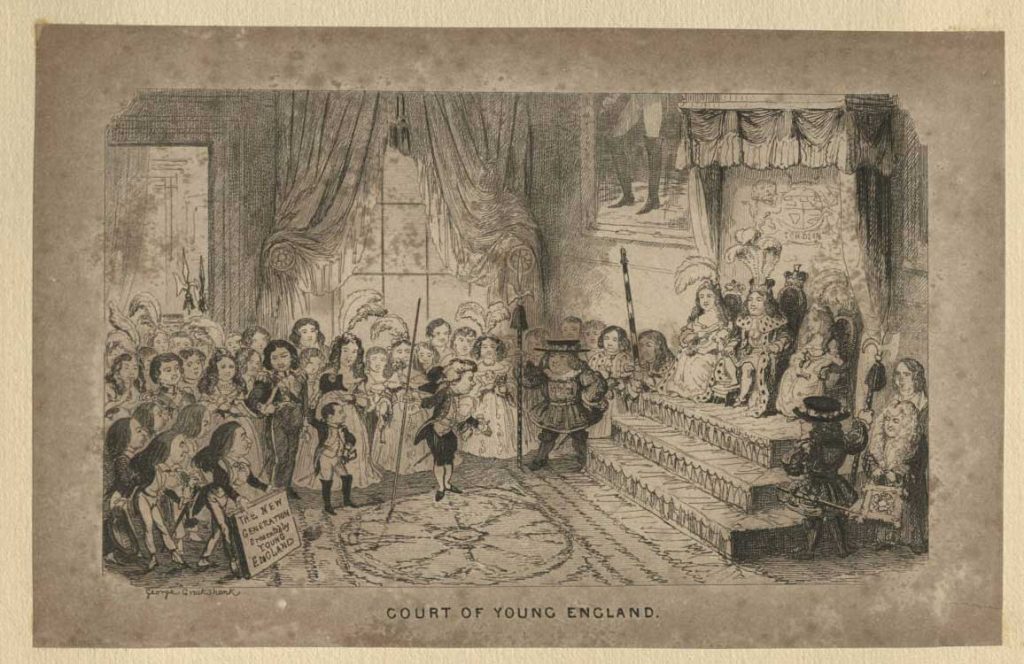

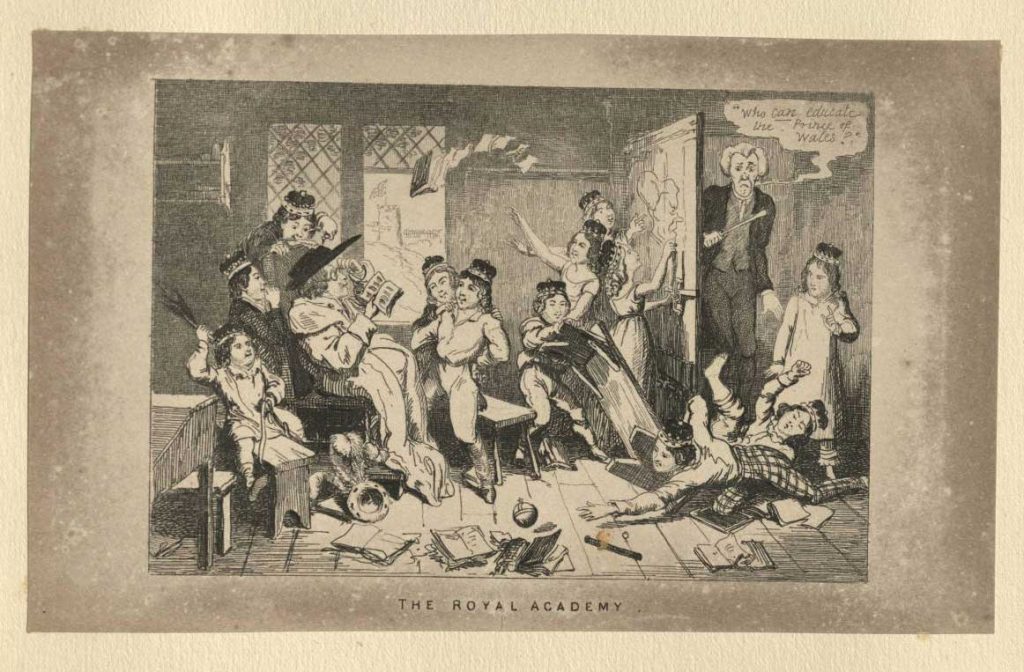

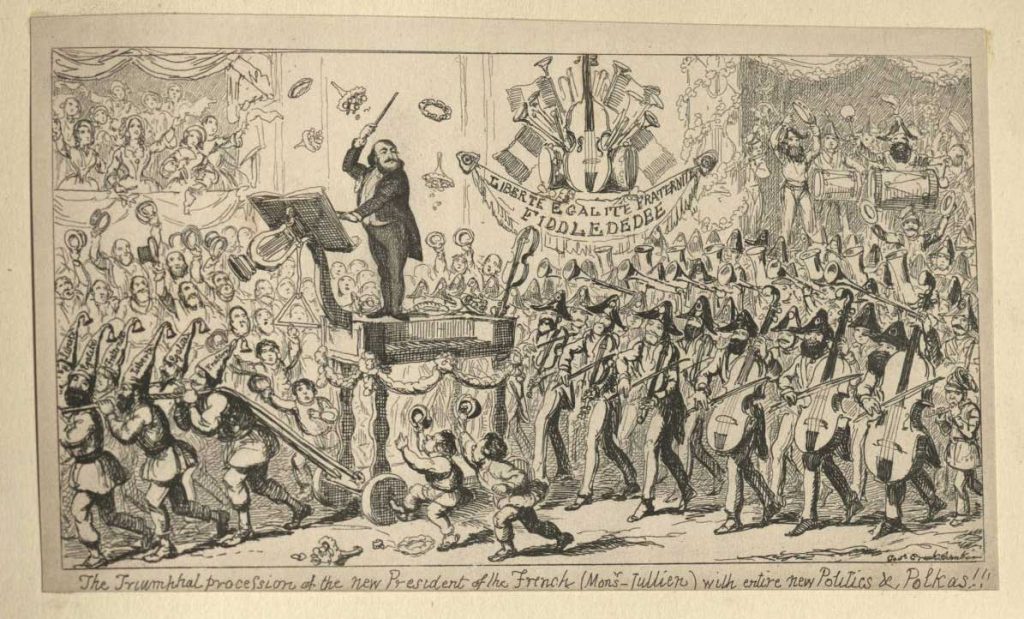

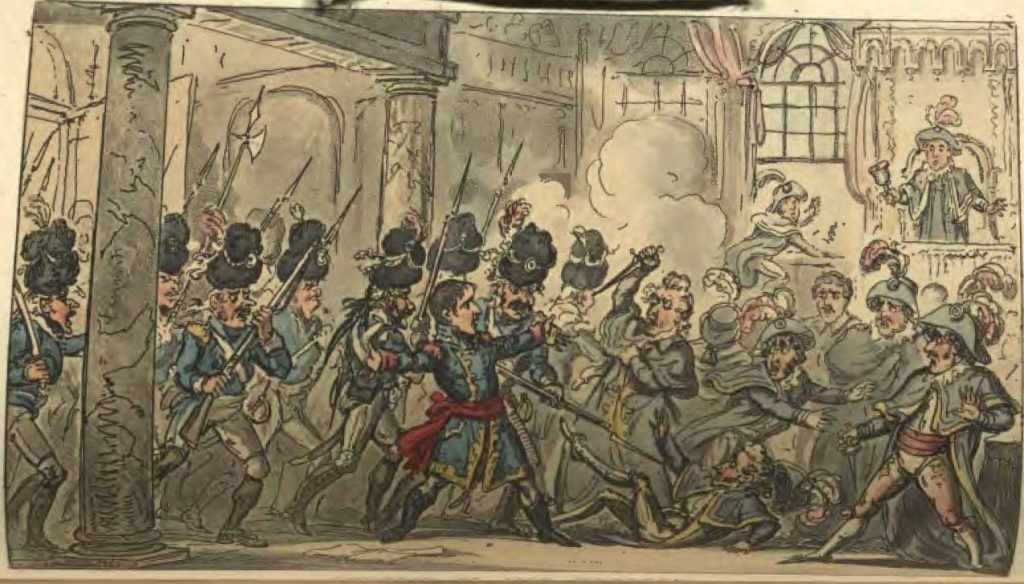

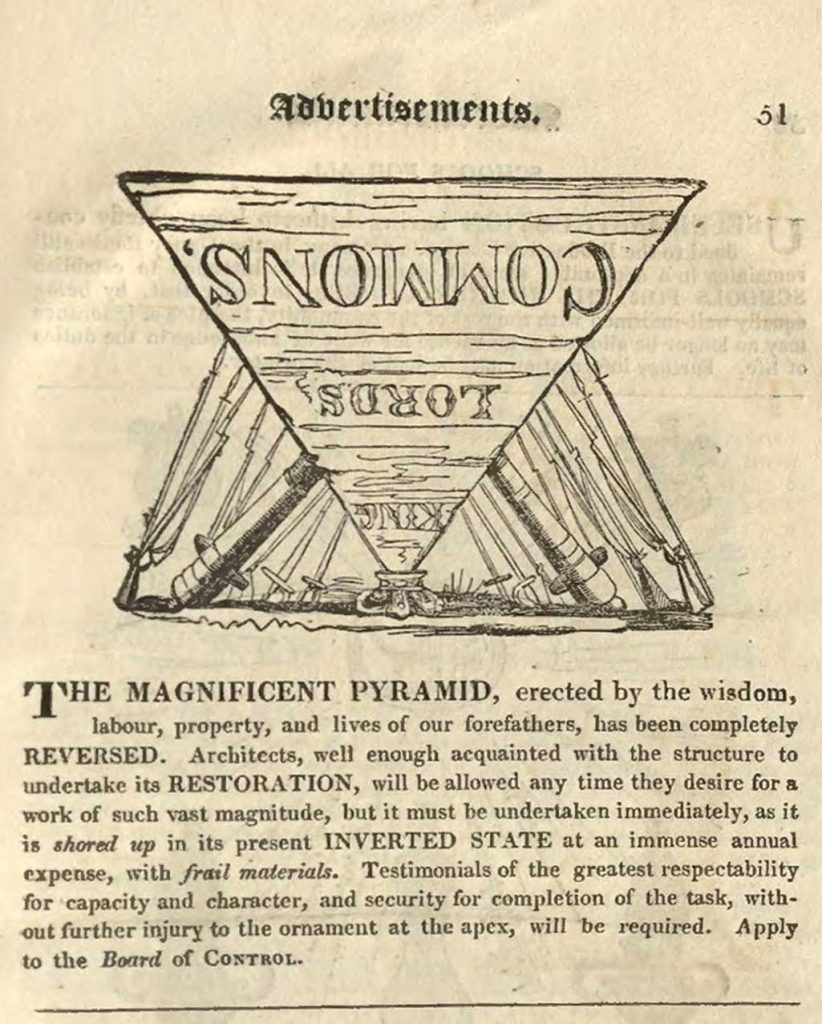

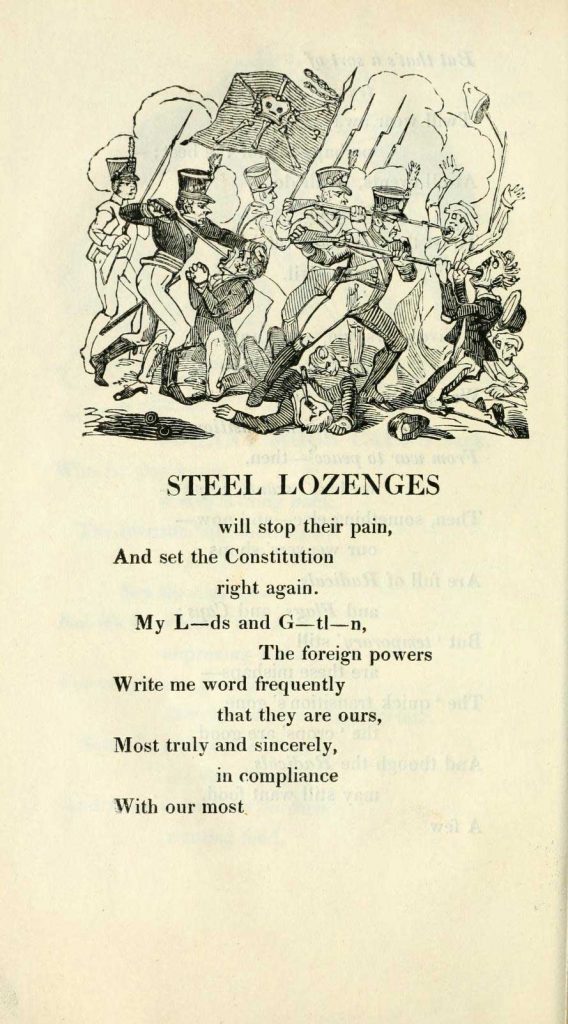

Cruikshank pulled few punches when it came to political satire. He took aim at both sides of an issue and tackled domestic political institutions, behaviors, and concepts, as well as British history and world politics. Indeed, as Robert Patten observes, Cruikshank’s political sketches “confound efforts to identify a single and consistent political or ideological commitment.”

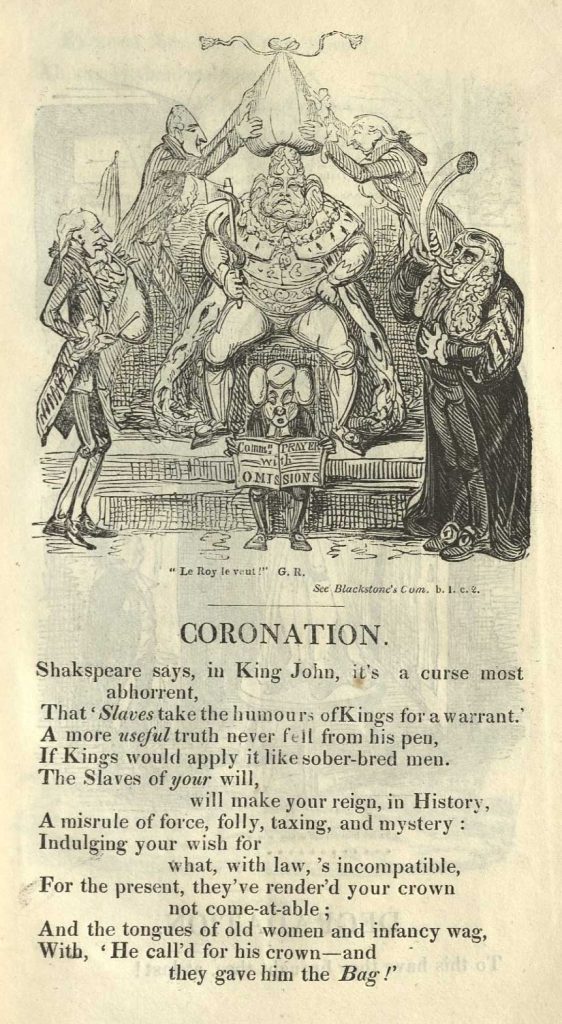

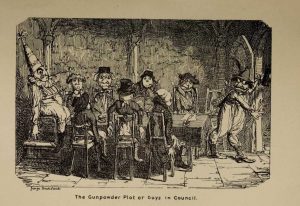

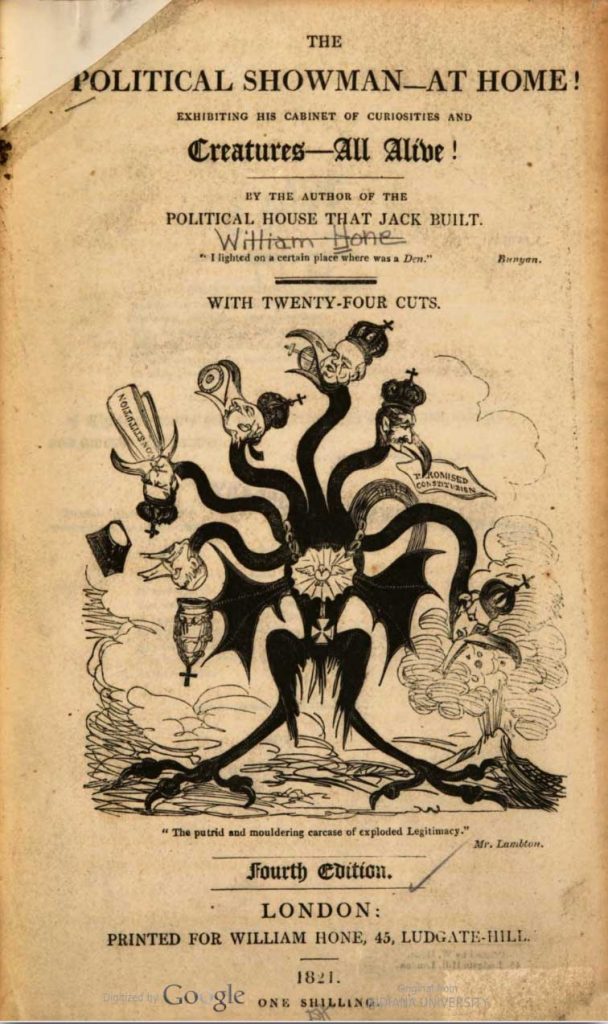

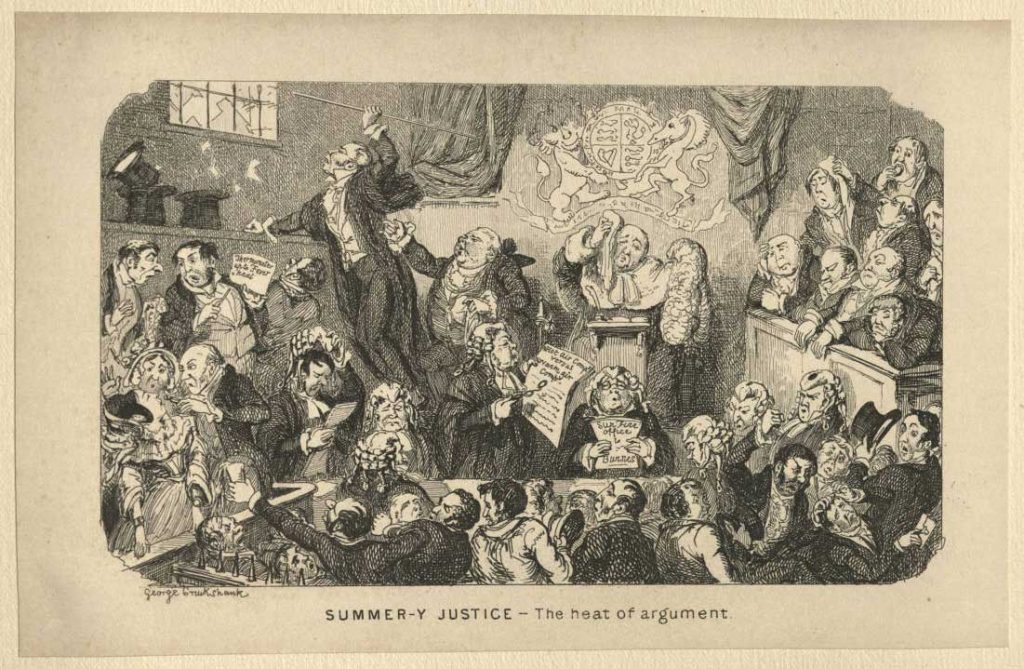

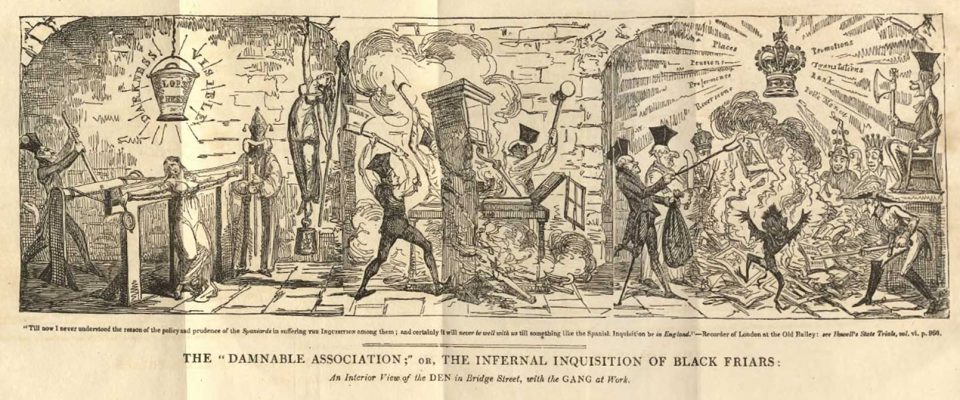

The images in this collection highlight the myriad of ways in which Cruikshank mocked political events, including his use of “grotesque,” exaggerated and disproportionate bodies, animals, and inanimate objects to represent political figures. Generally, Cruikshank relied on two techniques for his political satire. First, he tended to depict political figures as overweight and unattractive: he gave them disproportionately large bodies and unsightly facial features. Cruikshank’s rendition of political figures as slovenly is both metaphorical and comedic. Second, Cruikshank mocked politicians and their company by depicting them as animals or human-object hybrids.

Cruikshank illustrated political pamphlets and periodicals in the style of caricaturists James Gillray (1756-1815) and Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827), from whom he took up the mantle of graphic satire. Many of the images in this section come from collaborative works between Cruikshank and author/publisher William Hone (1780-1842). In 1817, the British government charged Hone with blasphemy, but the public was largely supportive of Hone and he was eventually found not guilty on all charges. Cruikshank’s collaboration with Hone includes The Queens Matrimonial Ladder (1820), The Man in the Moon (1820), The Political Showmen at Home (1821), and A Slap at Slop and the Bridge Street Gang (1822). As such, many of the images in this collection are also representative of Cruikshank’s early style before he established himself as a book illustrator.

These early satirical works also found a wider audience than the later, more “high brow” novel illustrations. Cheap pamphlets, papers and periodicals meant that satirical sketches and caricatures, like those featured here from the satirical Comic Almanack (an annual that ran from 1835 to 1854), not only reached a wider audience but spoke to their concerns.

“Throughout most of its run, the Comic Almanack cost two shillings and sixpence. At such a price, the Almanack would have been affordable not only by gentry and upper professionals, but also by clerks, small tradesmen, and even shop assistants.”

Frank Palmeri, “Cruikshank, Thackeray, and the Victorian Eclipse of Satire”

Playing on the widely popular genre of the almanac, a yearly overview of current events pertinent to a specific readership, The Comic Almanack featured many different writers including William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-1863), Albert Smith (1816-1860), and Gilbert A. Beckett (1811-1856). Within each edition, authors produced, “Merry tales, humorous poetry, quips, and oddities” that commented on Britain’s social and political climates. Working in wood engraving and copperplate etching, Cruikshank punched up and punched down, sometimes in the space of the same sheet.

Click on the images below to learn more about each sketch

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery