By Sheeza Kamal

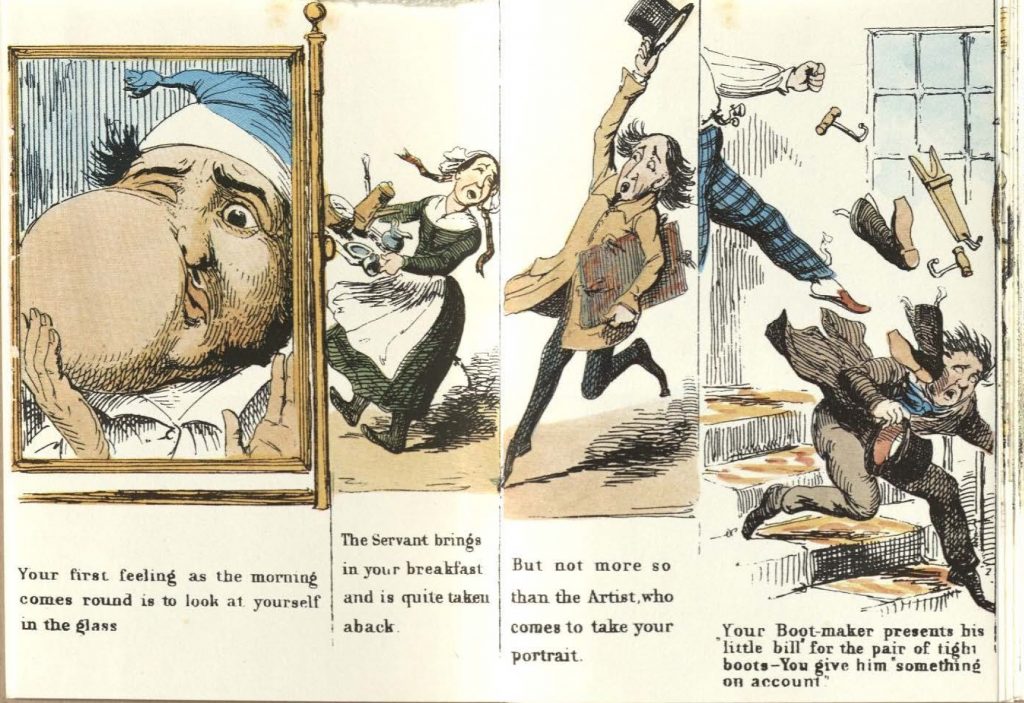

Have you ever felt immense pain that no matter what it cannot be fixed? Yet there comes a moment, may it be a millisecond when everything seems right in the world and you think, Aha! The world looks good again! And then that moment passes and you’re right where you started. It is that point in life where even a good joke seems far too superficial and annoying. But of course, there is always that one person that sees the joke in the pain, and in our case, that is George Cruikshank. There is no moment where the illustrator does not leave a moment to bring out his satirical self. The Tooth-Ache, as imagined by Horace Mayhew and illustrated by George Cruikshank is such a piece, that will leave you to admire their work and also put you in deep thought. The comic strip, which is hand-colored wood etchings, folds out in an accordion style from the covers and has forty-three numbered etchings.

Horace Mayhew was a journalist and sub-editor at the Punch, which is where George Cruikshank also started his career. He was a humorous writer, which is why he made the perfect candidate for a collaboration with George Cruikshank, as their take on society and societal issues resembled. Previously, George Cruikshank published illustrations that picked up issues surrounding alcoholism in society. His work related to the temperance movement is seen as one of the most crucial illustrations part of his career. Pillars of Ginshop illustrates and raises the question of how submission to alcoholism is demeaning and affects human life.

Mid-nineteenth century is when dentistry was something that was considered expensive and rudimentary at best. Without the advancements in medications and procedures that exist today, any dental ailment was considered a punishment. Even to the point of pulling one’s teeth out with pliers by blacksmiths who doubled as surgeons. The concept of dental hygiene and proper dental procedures come in the late 20th century. Pulling out one’s teeth without the use of numbing cream or gas? Ouch!

The extraction methodology is explained in the words of the famous Jane Austen in a letter, on one of her visits to the dreaded dentist. “The pelican was a brutal instrument with a pad or bolster, which was placed on the side of the gum below the tooth to be extracted and a beak or claw which engaged the opposite side,” the Jane Austen Center explains. “A downward twist of the handle tore the tooth out of the mouth. The key was similar, but had a handle similar to that of a corkscrew and enabled the instrument to be used more comfortably from the front of the mouth instead of the side.”

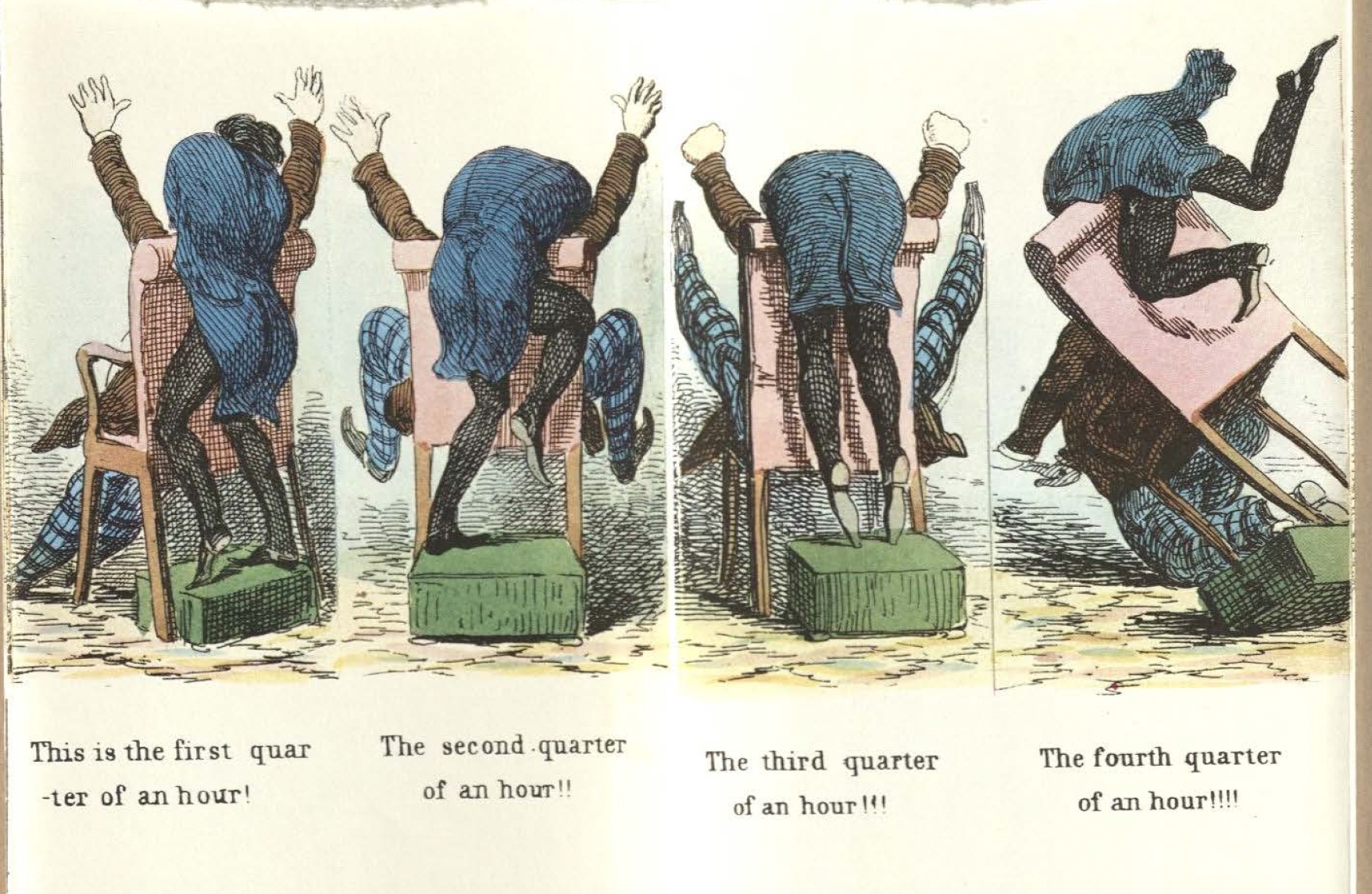

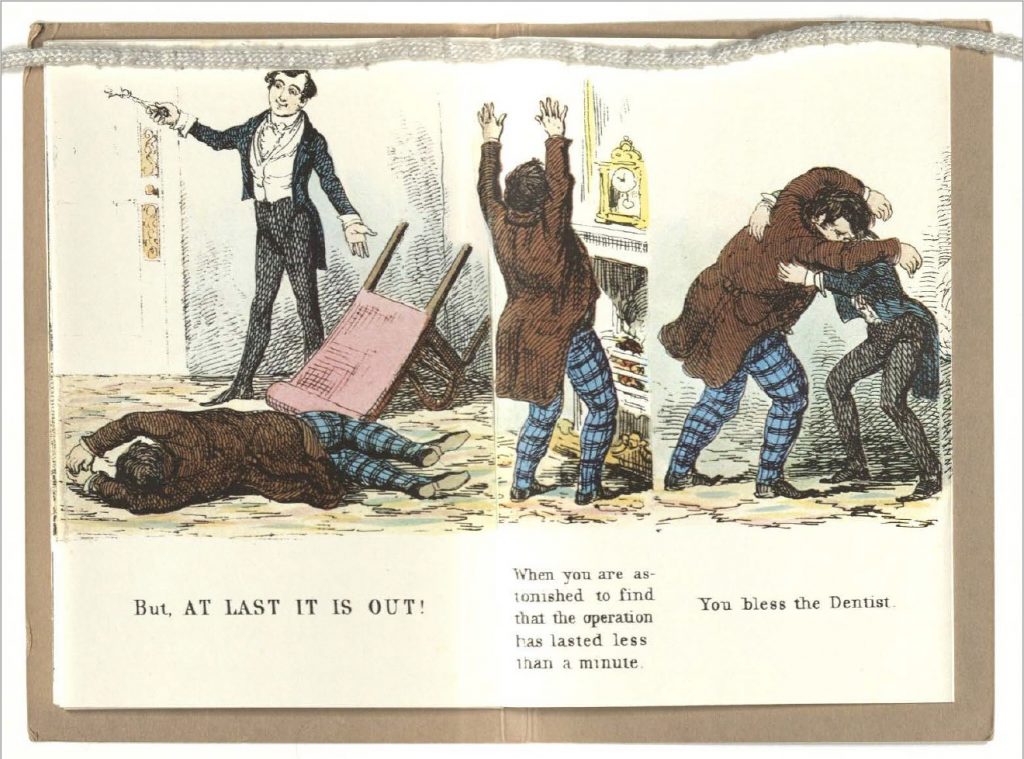

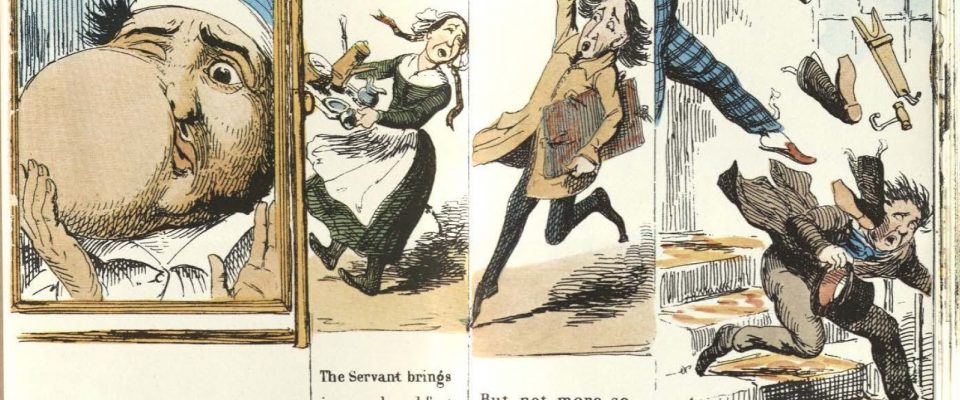

The comic shows exactly that. The character wakes up in the middle of the night with an intense toothache and trusts George Cruikshank to make the illustrations as comical and as exaggerated as they can be, showing off big swollen cheeks. The character throughout the forty-three frames is seen running all around his house and town to find moments of relief. It can be seen from his trajectory to try anything, except to go to the dentist, which of course plays upon the failing dental industry at the time. Frame 17 shows how despite the need, when the character is met by the dentist, the pain seems to go away. This is again a comical stance on how the dentist and their procedures did not use proper protocols for taking care of the patient’s pain, instead adding to it. At the time, the only effective way of getting rid of a toothache was to pull it out which we see depicted in frames 38 through 42. The relief and excitement that the patient gets after he receives the treatment can be seen through his celebratory movements.

George Cruikshank’s work on larger-than-life Britain and his take on the monarch can all be accessed through UMBC’s special collection under the Merkle Collection!

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery