In William Makepeace Thackeray’s admiring homage to Cruikshank in an 1840 Westminster Review article, he contends that Cruikshank’s political sketches are authentic because “he, living amongst the public, has with them a general wide-hearted sympathy; that he laughs at what they laugh at” including the “follies of the great.”

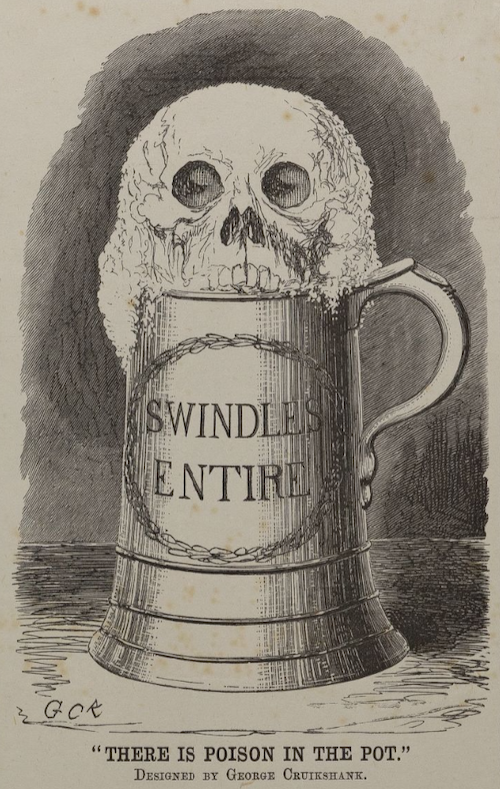

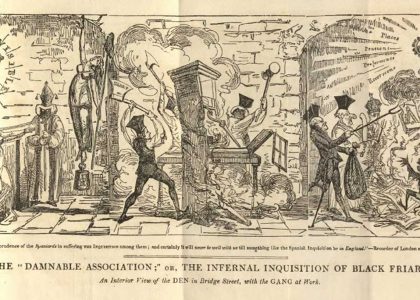

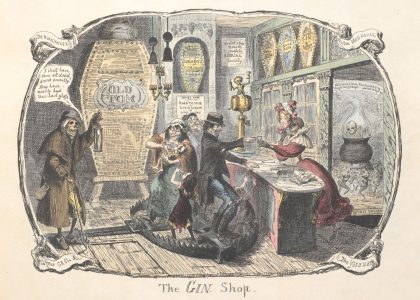

The items in this collection focus both on George Cruikshank’s work as a political satirist in his earliest years and as a prominent illustrator for the temperance movement in his twilight phase. Below, within the “Political Satire” collection, you will find Cruikshank’s inventive, thoughtful, and humorous depictions of political figures and events from the Regency and early Victorian eras. Within the “Temperance” collection, viewers will find Cruikshank’s captivating illustrations of alcohol’s influence on Victorian Britain, which include depictions of alcoholism and social decay.

Cruikshank’s political identity as an illustrator is ambiguous, sometimes frustratingly so. Regarding Cruikshank’s career as a political satirist, historian Vic Gatrell observes, “I think of him always as a chameleon…He was never really consistent in his politics and his morality” (BBC Radio 4). In his early years, Cruikshank earned money as an engraver and illustrator for commentators on the British political scene such as pamphleteer William Hone (1780-1742) and John Mitford (1782-1831), publisher of the satirical magazine “The Scourge.” Even earlier than this, he illustrated “Dr. Syntax’s” poetic Life of Napoleon (1815), providing 29 plates in which Napoleon is rendered practically in miniature. Following in a tradition of British graphic satire blazed by William Hogarth, James Gilray, and Thomas Rowlandson [see Contemporaries page], Cruikshank managed to find his own style.

While Cruikshank’s political beliefs are difficult to summarize, his tendency to portray members of the royal family and other famous political figures as power-hungry, emotionally erratic, and extravagantly dressed demonstrates an artistic drive to highlight the madness and opulence of British politics. From lampooning the crown to judging society’s self-indulgent spirit sipping, Cruikshank’s sketches shone a light on the political and social questions that punctuated mid-century London. Indeed, as contemporary biographer Robert Patten observes, Cruikshank leaned into “the subversive freedom of etching contradictions into the copperplate.”

One cause to which Cruikshank was unambiguously dedicated in his later years was temperance. Prior to his sober turn in the late 1840s, “surely no man drank with more fervour and enjoyment” biographer Blanchard Jerrold exclaimed. Cruikshank developed a great interest in illustrating for the temperance movement after struggling with alcoholism as a younger man and watching his father, brother and Gillray succumb to premature deaths. In fact, Jerrold suggests that Cruikshank was converted by his own sketches for the 8-plate glyphographic series The Bottle, transitioning from occasional sipper to zealous teetotaler. This dramatic shift in lifestyle and the horror captured within his engravings of alcohol’s effect on the entire family makes his temperance sketches all the more captivating.

Click on the images below to explore each collection

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery