By Reilly Robertson

The Victorian Era straddles the Industrial Revolution, which sparked advancements in literature, clothing, print, and fashion. George Cruikshank’s bound book of sketches labeled “My Sketch book” is one of the many items in special collections that UMBC has to offer for people interested in studying Victorian Era caricature and lifestyle. Some of the sketches from his sketchbook depict women from these times, specifically from 1792 to 1878, when his sketchbook was being used. Around 1790, the sewing machine was introduced into England, changing the clothing production from hand-sewing to industrialized.

Fashion can show historians and history buffs great changes and revolutionary aspects of a growing culture. Even in the modern age, clothing signals a person’s status or wealth and can change the way they are treated. Changes in dress can occur based on trends and then become cemented, even during the late 1700’s way before the internet.

Citizens dressed based on job title and class. Nowadays, we wear casual clothing, but in the 1700-1800’s there were only two options: dress or undress. Undress was a gown or robe that women wore in the evenings at home. It wasn’t until the latter part of the 1800’s that clothing brands became widespread and mass produced.

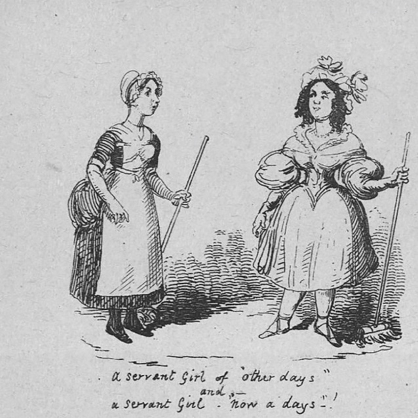

Not all women dressed in the luxurious way people often associate with fashion from England; in fact, most women wore practical clothing. In the image above, there is a depiction of two servant girls, one dressed from Cruikshank’s time, one from years earlier. Likely, this is a commentary from Cruikshank on the changes that had taken place in clothing since the beginning of the industrial revolution. Both women are wearing mob caps, which were circles made from cotton to keep hair out of the way. However, the mob cap on the right is bigger, and less useful, satirizing the style of such clothing for a maid. A very common job for women at this time was to be a servant or a maid, and the outfits they would’ve worn would resemble those pictured.

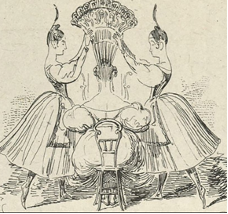

This sketch is a symmetrical portrayal of a mistress lady, with two maids helping her put on a large hair comb. A ‘lady’s maid’ was a job for women. Maids who had proven themselves competent enough servants to get a higher paying position could receive a job with perks. A lady’s maid would have her own room, a full wage, and would also go on trips with her mistress. The reason why the maids here may be pictured as similarly dressed is because the lady’s maids often would receive their mistress’ unused clothing, meaning that would be dressed as an upper class citizen.

The two women pictured here in the center of this sketch are both wearing dresses that provide an hourglass shape, clearly attracting the attention of a gentleman behind them. One also adorns an aiguillette, which is a long braided cord that represented appointment in the Napoleonic Wars, but civilians copied this as a stylistic trend. Decorative hats such as the ones pictured would’ve been only for the upper class, and were popularized by Marie Antoinette due to increased trade with Africa. Ostrich feathers were popular due to Antoinette’s adoration of them.

Analyzing historical fashion is one of the ways researchers can study events from centuries ago, and will likely be the way researchers study us in the future. Cruikshank, although credited for being a caricaturist, can also teach us about culture through his sketches and portrayals of women during his days.

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery