By Emma Jett

Advertisements for magical health and wellness pills or supplements are something that we routinely encounter as we scroll through social media, read online articles, or watch TV. At times, the advertisements seem too good to be true with the claims that all of our health problems could be fixed for the low price of $39.99. While these companies make broad claims about their supplements, most of these products are glorified multivitamins or laxatives which would not actually help the consumer. However, people who are either unaware of this or desperate to find relief from their medical ailments are persuaded to purchase these supplements.

The presence of these pseudo-medications is not unique to the 21st century. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw a multitude of “doctors” who would travel around both the United Kingdom and the United States selling magical elixirs and universal cure-alls to people who were otherwise naïve to their motives. These snake-oil salesmen, as they came to be known, would continually rake in considerable profits from the people they swindled, knowing that they were selling false-hope, not a cure.

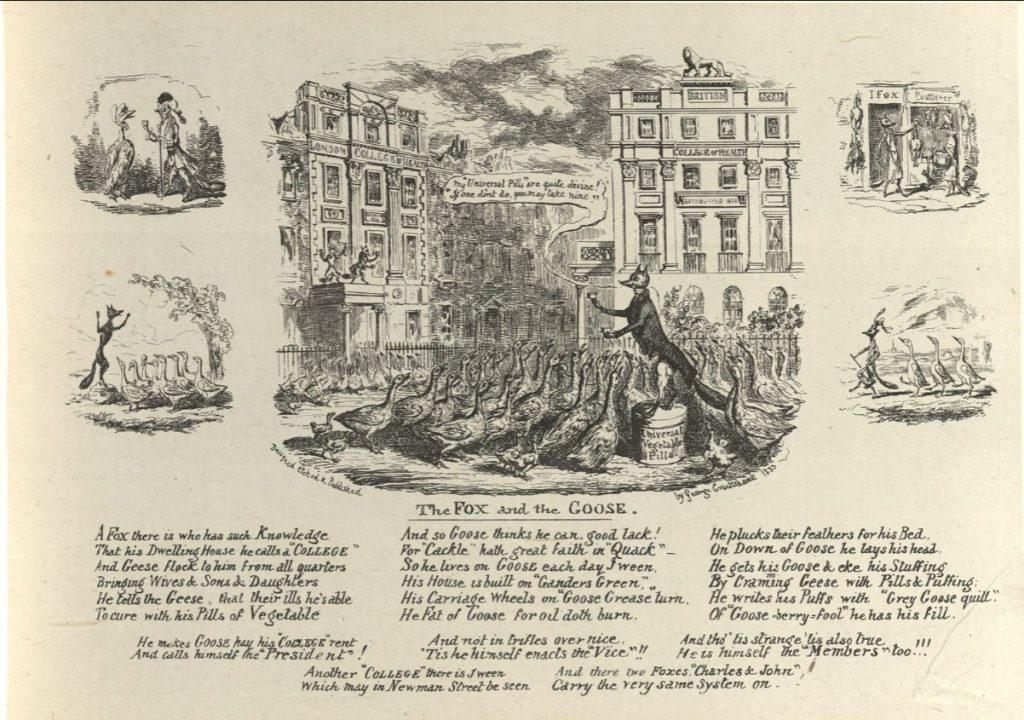

George Cruikshank’s “The Fox and the Goose” shares satirical commentary on these snake-oil salesmen and their elixirs’ impact on 19th-century Britain. “The Fox and the Goose” is a large etched illustration that was “designed, etched & Published” by George Cruikshank in 1833, as seen etched under the central image on the page. This item is found in the collection of his work titled “My Sketch book” and features a central image, four smaller ones, and a narrative poem that gives context to the sketches.

The pseudo-doctors that George Cruikshank critiques would benefit both financially and reputationally through the scamming of common people who didn’t know any better than to trust someone who seemed to have the right qualifications (such as being connected to a college, as the fox was) to provide medical advice. George Cruikshank, however, raises the stakes of this swindling in the satire of this etching by showcasing the fox’s benefit from the dead goose body, fattened as a result of the universal vegetable pills.

George Cruikshank chose the fox, traditionally depicted in art and literature as a devious and cunning animal, as the focus of this print. In the central image, the fox dons a respectable waistcoat, standing on a large case of his “Universal Vegetable Pills,” with the full and lively attention of dozens of geese surrounding him. In front of the London College of Health, the fox tells the onlooking geese: “my ‘Universal Pills’ are quite divine! If one don’t do, you may take nine!” Being respected as a creature of knowledge – so much so that the poem reveals that the fox’s house itself was known as “a ‘College’” – the geese believe that the wise fox is correct in his assertions that he has come up with a cure for their medical ailments. The viewer, however, recognizes that a simple vegetable pill could not truly serve any medicinal purpose, let alone act as a cure-all that the fox presents to the naïve geese.

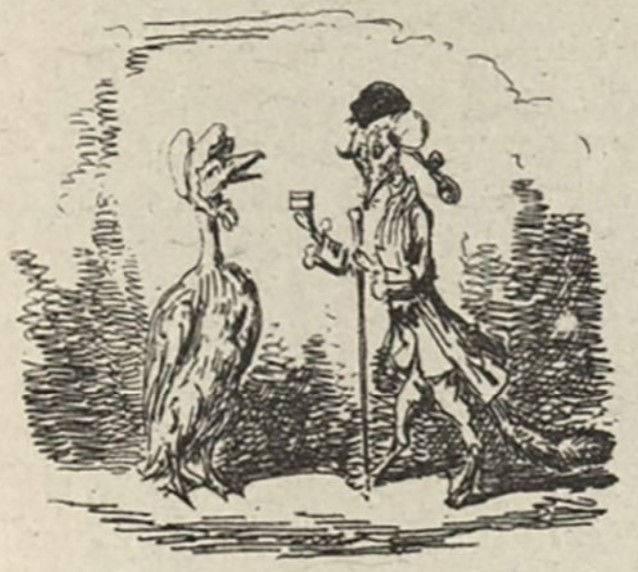

In the images that surround this scene and the narrative etched underneath them, we learn that the trust that these geese put in the fox and his pills ultimately leads to their demise. In the upper-left illustration, we see the increasingly well-dressed fox offering a box of these pills to an elderly goose wearing a bonnet and glasses.

Below, the fox stands on a rock in the woods, speaking to a flock of geese – while he isn’t dressed in his respectable clothing, we see that he continues to hold the interest of the geese.

In the bottom right, we see the fox dressed in a military outfit, with three geese marching in step with him, following from behind to an unknown destination. With these three illustrations, then, George Cruickshank is able to showcase the depth to which the fox has cunningly won the trust of the geese through his persuasive powers and his pseudo-cure for their ailments. The geese believe that the fox and his miraculous pills work, when in fact they have no medicinal use.

![A close up image of the smaller illustration on the top right side of the page. A fox in an apron holds a plucked dead goose in front of J. Fox Poutleres [sic], which has several other dead geese hanging in the window. The fox is selling this goose to another fox dressed in a nice dress and hat and carrying a market basket.](https://library.umbc.edu/specialcollections/cruikshank/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2022/10/Fox-upper-right.jpg)

Rather than giving the geese anything that would actually aid them in their various situations, the vegetable pills would only result in the fattening of the goose taking them. The fox, of course, knows this and encourages the geese to take a multitude of them if they think that a smaller dosage isn’t sufficient for their ailments. The fox also knows that the pills would make their situation worse. This leads to the death of the fattened goose, shown hanging in the windows of J. Fox’s “Poutlerer” [sic] in the upper-right image.

What the geese are unaware of is that the fox – a natural predator of the goose – is profiting off of the sales of the pills as the geese buy them, and he’s profiting off of their deaths. The fox uses just about every part of the goose corpse for his own gain and comfort, and other foxes can be seen in the central image of the background, leading other geese astray in a similar fashion.

Through this illustration George Cruikshank reveals the presence of the snake oil salesmen, like the fox, in his community. While the fate of the goose is rather grim in “The Fox and the Goose,” he opens up the conversation surrounding snake oil salesmen to consider the degree of impact that their manipulation has on common people. Are they harmlessly selling their products, or can the reach of their influence lead to some realities that mirror that of the goose?

More information on snake oil salesmen in the nineteenth century can be found here:

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery