“Am I stilted or turgid when I paraphrase that which Johnson said of Homer and Milton, in re the Iliad and Paradise Lost, and say of Hogarth and Cruikshank that George is not the greater pictorial humourist our country has seen, only because he is not the first?”

George Augustus Sala’s William Hogarth: Painter, Engraver, and Philosopher, 1866.

Cruikshank’s motifs, style, palette, scale and methods were not entirely his own. He was indebted to a line of graphic satirists before him. This page features a few of the artists that are part of Cruikshank’s visual genealogy.

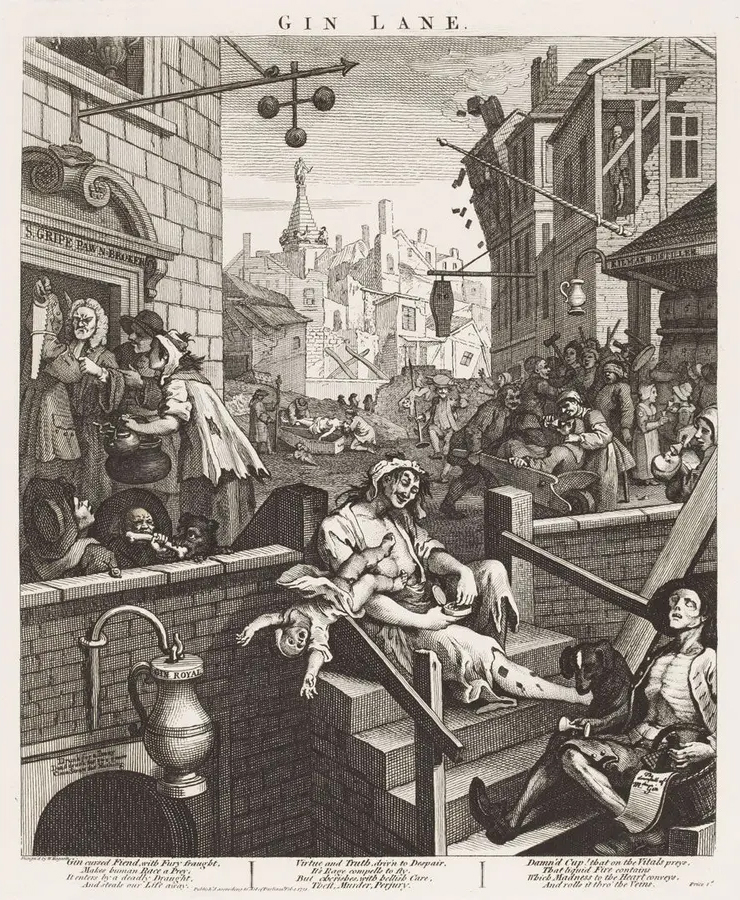

William Hogarth

Britain’s nineteenth-century caricaturists and illustrators were deeply influenced by William Hogarth (1697-1764), the most important illustrator of the eighteenth century. His influence is unmistakable on Cruikshank especially who also used odd, absurd, or mildly offensive situations in his art to critique society. George Cruikshank admired and mimicked Hogarth so much so that Cruikshank’s temperance series “The Bottle,” was perceived as a modern version of Hogarth’s famous series “Industry and Idleness.”

The engravings created by the two were fully finished in detail which reflected their dedication to their work. Like Hogarth, Cruikshank strived to eradicate the use of alcohol through revealing the damages gin inflicted on the people. For more on Hogarth and his influence on Cruishank’s art, check out the blog “George Cruikshank’s Vision of a Gin-Crazed Britain.”

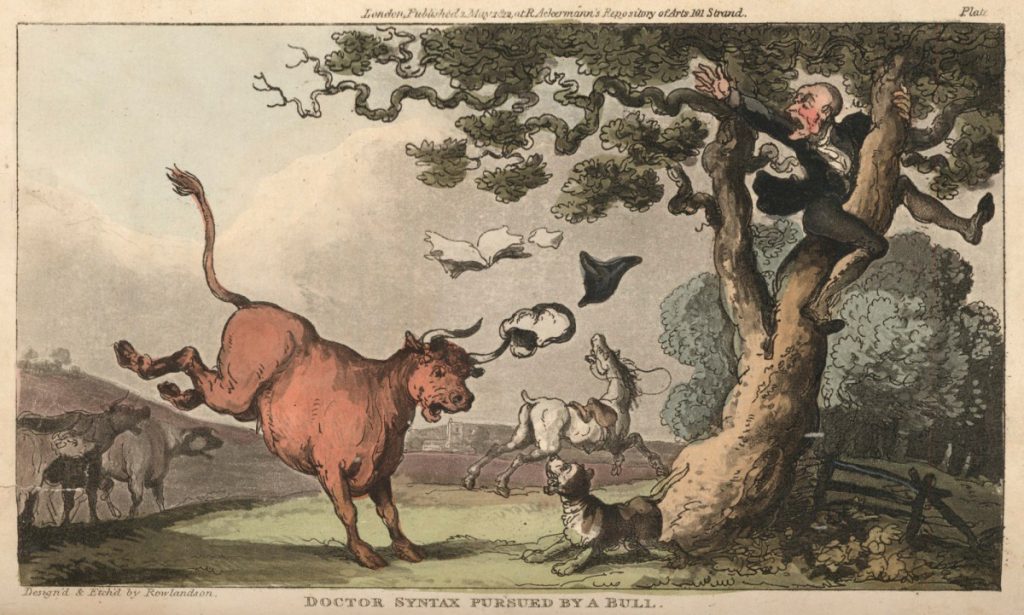

James Gillray & Thomas Rowlandson

Before Cruikshank rose to prominence, James Gillray (1756- 1815) and Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827) were known as “the fathers of political cartoons.” They created bawdy satirical images and political cartoons that captured the popular imagination of the British people, lampooning the politicians and monarchs of the day, even foreign leaders such as Napoleon. In addition to his engravings, Rowlandson worked in watercolor and created “high art” pictures. Gillray was primarily an etcher and worked in aquatint; his political sketches were frequently aimed at King George III and he was adept at social satire as well. Once Gillray became severely ill with gout (and his eyesight was fading), he commissioned Cruikshank to complete his unfinished plates. Their styles were perceived to be nearly identical at the start of Cruikshank’s career.

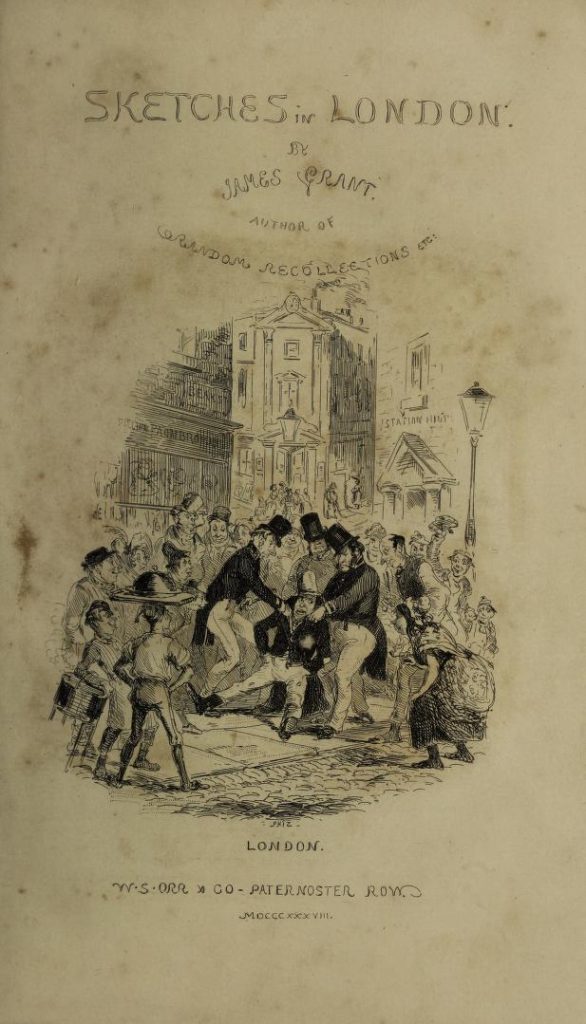

Hablot K. Browne (Phiz)

Working in the same years as Cruikshank, Hablot K. Browne (1815-1882), adopted the name ‘Phiz’ to sound like Dickens’ ‘Boz,’ and his star rose alongside Charles Dickens for whim he illustrated Pickwick, David Copperfield, Bleak House and others. Phiz and Cruikshank’s images for Dickens even inspired stage versions of these novels and stories. His work was published widely in magazines, including the long-running satirical periodical Punch, and he preferred etchings on steel (whereas Cruikshank tended towards copperplate engravings).

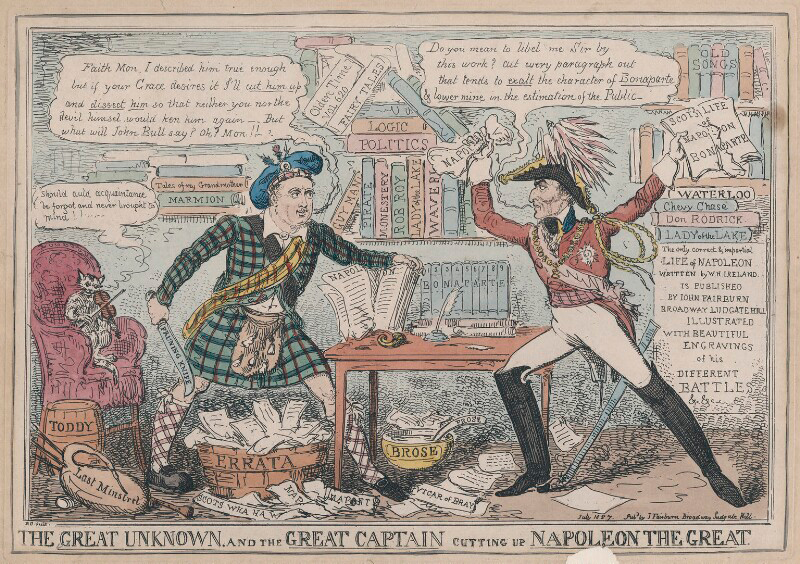

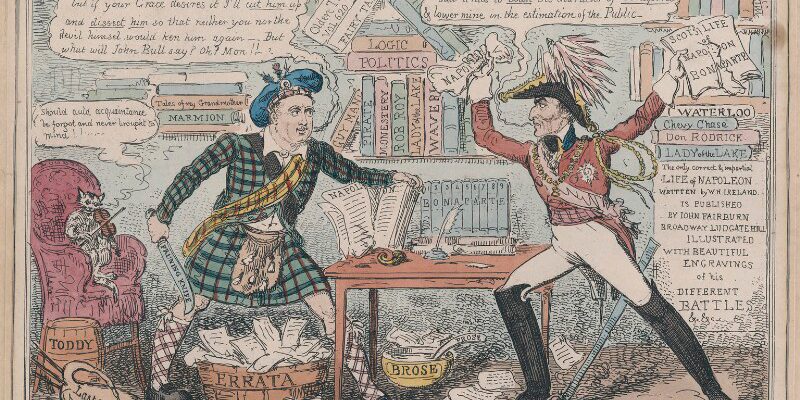

(Isaac) Robert Cruikshank

Though George would become the most famous Cruikshank engraver, his brother Isaac Robert (known as Robert) (1789-1856) was equally creative as a caricaturist, illustrator, and portrait miniaturist. As Cruikshank, Robert followed in his father’s footsteps and published cartoons that were extremely popular with the British public. As this image makes clear, both brothers took up the mantle of political commentary from their father and the visual motifs of Regency-era graphic satire. For more on Cruikshank’s political sketches, visit the Political Satire collection.

Richard Doyle

Richard Doyle (1824-1883), also known as ‘Dicky’ and ‘Dick Kitkat,’ was drawn to the fantastical, depicting fairies, demons, and imaginative landscapes. He was particularly adept at illustrating children’s books. Doyle published extensively in Punch, where he followed in Phiz and Cruikshank’s footsteps as a satirist. Though he illustrated for some novelists like Thackeray, his forté remained the whimsical world of fairies. You can can read more about Cruikshank’s work in the fairytale genre here.

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery