By Megan McIntosh

Following the eighteenth century, an era of excessive drinking, some British citizens, George Cruikshank included, began to associate drinking with the downfall of the working man and his family. These concerns developed into the temperance movement and the more radical teetotaler movement.

The temperance movement began with the belief that alcohol should be used in moderation, mostly advocating against drunkenness and the overindulgence of liquors. Teetotalers, however, believed that one should completely abstain from drinking any type of alcohol.

George Cruikshank was a heavy drinker until the age of 55. However, in the latter half of his life, he became a teetotaler who was adamantly against drinking and his disdain for alcohol is apparent in several of his engravings.

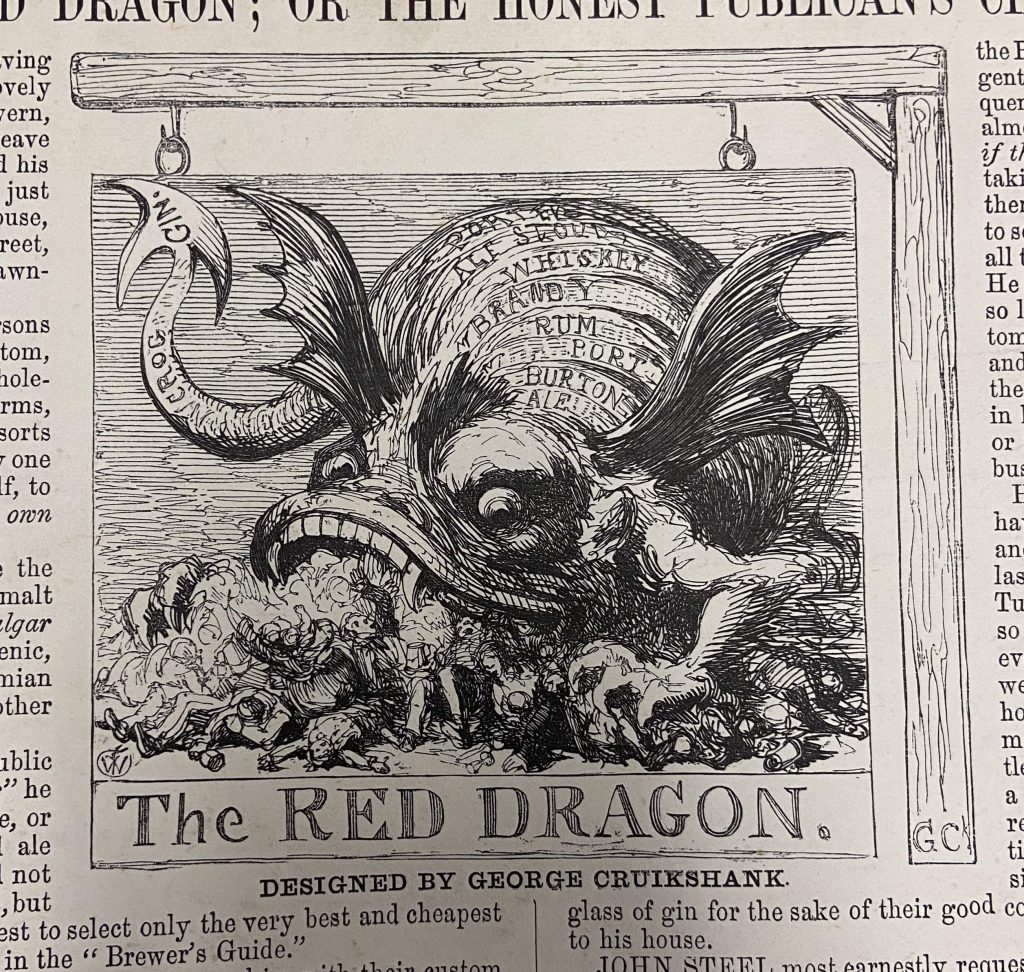

“The Red Dragon” is an engraving designed by George Cruikshank featured on an 1852 temperance placard published by William Tweedie in London. The Red Dragon was a popular public house at the time. In this illustration, George Cruikshank depicts the Red Dragon as just that: a dragon. The beast is huge and has sharp teeth and a tail resembling a devil’s. It squashes people under its hands as it feasts upon others. Along the dragon’s back are the names of multiple types of alcohol and several of the creature’s victims are grasping mugs or bottles, thus depicting how alcohol is bringing about the customers’ ruins and serving as an anti-advertisement for the pub.

“There is Poison in the Pot” is another illustration designed by George Cruikshank. It is featured in a different placard of the same William Tweedie series. It depicts a foamy skull in a mug labeled “SWINDLES ENTIRE,” suggesting the way that alcohol is both a deceiving waste of money and potentially fatal. Interestingly, a lot of illegal gin around this time actually did have poison in their pots; some bootleggers in the 18th century sold gin that was flavored with turpentine or even sulphuric acid.

“Home in Shadow” is yet another engraving from William Tweedie’s placards. In this engraving, George Cruikshank depicts what is perhaps the most disheartening effect of drunkenness: the harm it does on the family. Many teetotalers argued that alcohol could transform a kind, hard-working man into an abusive household tyrant.

In this illustration, a man comes home drunk and seemingly violent with his fists raised and mouth open, possibly spewing profanities. The moon in the window, the candle on the table, and the children in bed signify that the man has come home extremely late. The fear on the one child’s face and the mother’s sad frown indicate that he is likely abusive or, at the very least, mean and incoherent. The house is also small and mostly empty, perhaps to signify that the man’s behavior has affected his work and, thus, their financial well-being, too.

The depictions George Cruikshank designed may seem dramatic or exaggerated, but the temperance movement followed a large surge of drinking in London, often referred to as the gin craze. By 1751, the annual consumption of gin in England and Wales reached 7.05 million gallons, roughly one gallon of gin per person.

During this craze, there was a rise in crime and death rates and a fall in birth rates. Individuals from all classes were socially encouraged to drink. This period also marked the first time that women drank alongside men. Gin at the time was often referred to as “mother’s ruin” due to the increasing number of mothers who turned to drinking and neglected their children.

Furthermore, alcohol was occasionally prescribed as medication for both physical and psychological illnesses until the twentieth century. By rebranding alcohol as a “tonic,” alcohol producers were able to increase sales and consumers were able to convince themselves drinking was healthy.

Although the gin craze ended about fifty years before the temperance movement began, alcohol remained an integral part of everyday life for men and women of all classes. Thus, although George Cruikshank’s passionate feelings about the damage that alcohol could inflict on a person’s morals and family may sound extreme now, they weren’t unwarranted at the time.

Over the years, Gin Acts were enacted. However, the government was mostly concerned with the drinking habits of the working-class and didn’t want to enact laws that would infringe on the ability for the middle and upper classes to purchase and consume alcohol. There was also a strong debate about whether the state should be able to interfere with private enterprise.

Therefore, some teetotalers, like George Cruikshank, used placards like these ones that appealed to the individual in an attempt to motivate personal change. However, despite the teetotalers’ best efforts, the temperance movement mostly came to an end during the twentieth century.

You can view and read the full scans of the temperance placards featured in this collection in the UMBC Digital Collection.

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery

Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery