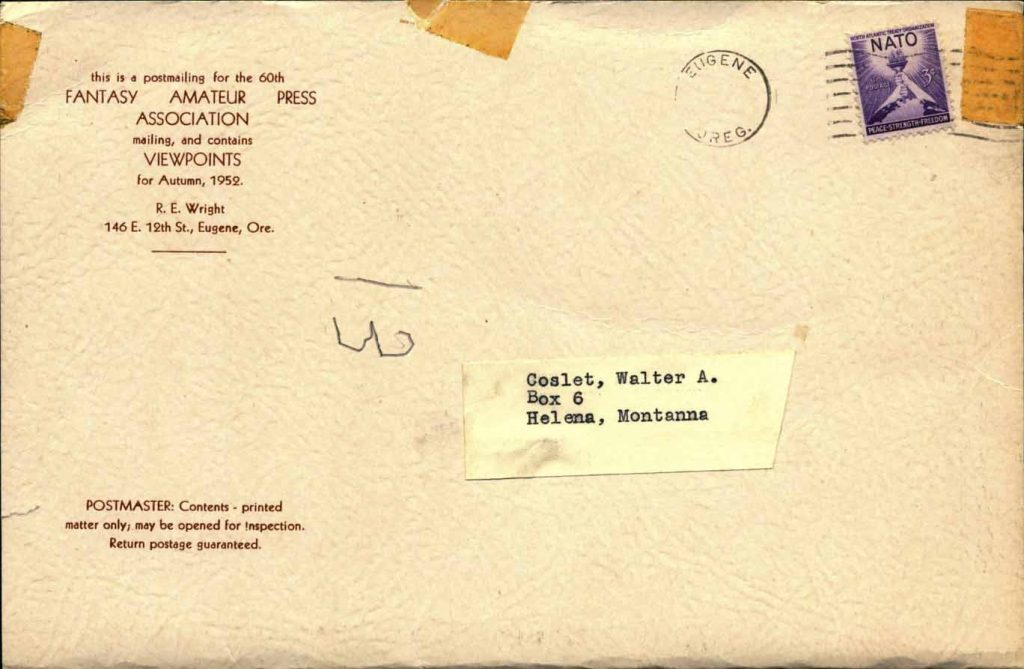

The Coslet-Sapienza Fantasy and Science Fiction Fanzine collection is comprised of over 15,000 fanzines that date from 1937-1972, and there are tens of thousands of fanzines altogether at Special Collections. Walter A. Coslet was a science fiction (SF) enthusiast who collected and published an array of SF fanzines. Coslet’s personal collection was once held in Portland, Oregon, but now his collection resides in the Special Collections department at UMBC. Peggy Rae Sapienza was also a SF fan, publisher, convention runner, and former UMBC student who donated her personal SF collection to UMBC. The Coslet-Sapienza collection contains not only fanzines, but a number of amateur press mailings that provide insight into the workings of the SF fanzine fandom. By researching fanzines, we can come to understand the inner workings of the SF fanzine community and ultimately have a broader understanding of what alternative culture can mean. The Coslet-Sapienza collection highlights how the SF fandom networks, their means of production for creating fanzines, and their use of amateur press associations to distribute their work.

Fanzines can be defined as “noncommercial, nonprofessional, small-circulation magazines which their creators produce, publish, and distribute themselves.”1 The first fanzine was inspired by Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories, which was the first SF magazine. The decision by Gernsback to print the addresses of SF fans spawned a surge of communication between fans who went on to create amateur publications through the fanzine medium. The first fanzine was called The Comet (1930-1933) and was created by Raymond A. Palmer and Walter Dennis.2 Since the beginning of SF fanzines there have been a number of other genres of zines that cover topics such as music, politics, television, film, sports, art, religion etc.. Fanzines often have a single editor but in some cases there are various people working on a single fanzine. They can either run for a single issue or continue to print dozens of issues over the course of years, but much of this is due to constraints on funding, material, time, or other mixed restrictions. The aim of fanzines is not about turning a profit; in fact fans often lost money from producing and distributing their zines. Instead the motivating factors of the SF fandom were out of pure love of SF and wanting to build relationships with people who have similar interests. It may be easier now to come across someone who likes SF, but during the early days of SF fandom there weren’t a lot of options for fans to come into contact with one another.

The element of SF fanzines and fandom that is especially fascinating relies on the understanding of community and alternative culture. SF as an entire genre has certainly become more mainstream over the years, but this wasn’t always the case. To look at the history behind the early fans of SF and their zines demonstrates how people take action in order to see the kind of change they want to see in the world. Creators produce zines because they want something authentic and free from top down management that would have limited them from sharing precisely what they want.3 In the case of SF fandom they had a monumental, and fair to say, obsessive passion for SF. They didn’t feel like they were getting enough of what they wanted about SF from popular culture or their local communities. The stories, art, ideas, opinions, representation and support that circulates in this fandom has nourished the livelihood of fans for years, and is still very much present today.

- Duncombe, Stephen, “Zines,” in Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture (London: Verso, 1997), 6. ↩︎

- “Cosmology.” Fancyclopedia, 10 Jan. 2018, http://fancyclopedia.org/cosmology. ↩︎

- Duncombe, Stephen, “Identity,” in Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture (London: Verso, 1997), 32. ↩︎