By Rebecca Wireman ’18, media and communication studies

Janus/Aurora Fanzine and Feminist Science Fiction

Science fiction and fantasy fandom always had a boys club feel despite the consistent presence of women fans who were involved with fandom in one way or another. There have been many a great women SF writers, publishers, editors, and fans throughout history. Ursula K. Le Guin, Alice B. Sheldon (a.k.a James Tiptree Jr., or Raccoona Sheldon), Octavia E. Butler, Margaret Atwood, Joanna Russ, and Marion Zimmer Bradley, are just a few of the countless number of women that have contributed to speculative fiction1 and SF fandom. As the New Wave movement2 in SF rolled around during the 60’s and 70’s, so did a new era for women SF fans and authors. The radical change seen in second-wave feminism prompted the women of SF fandom to carve out more of a space from such a male-dominated community.

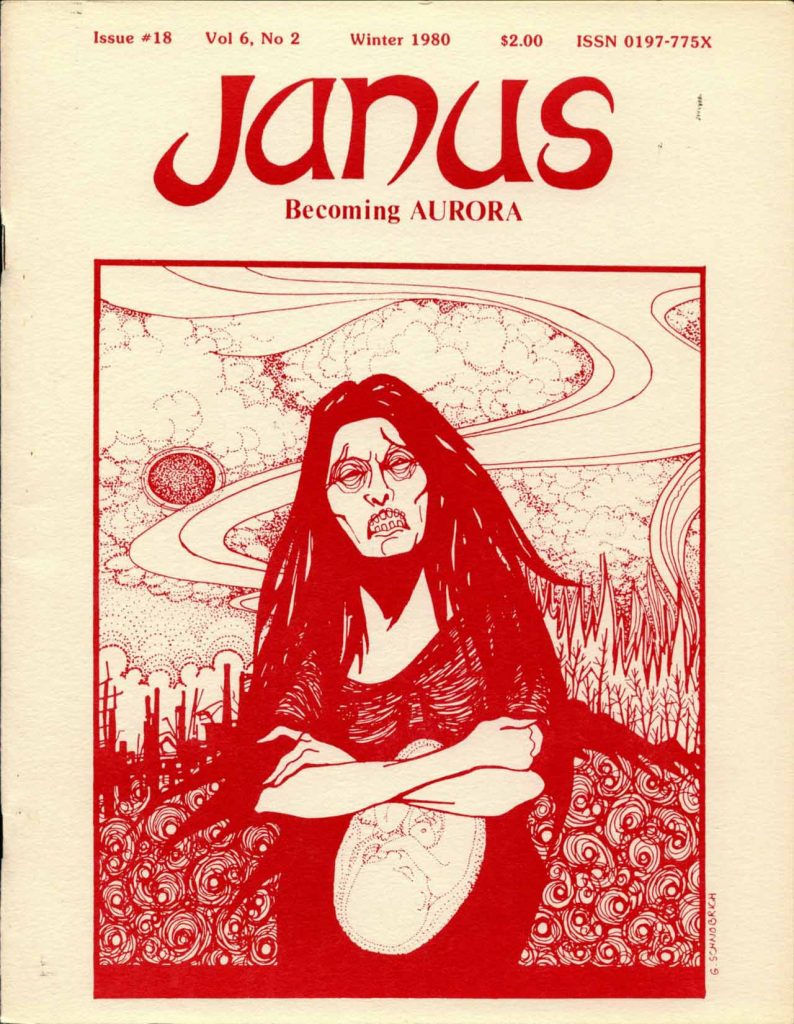

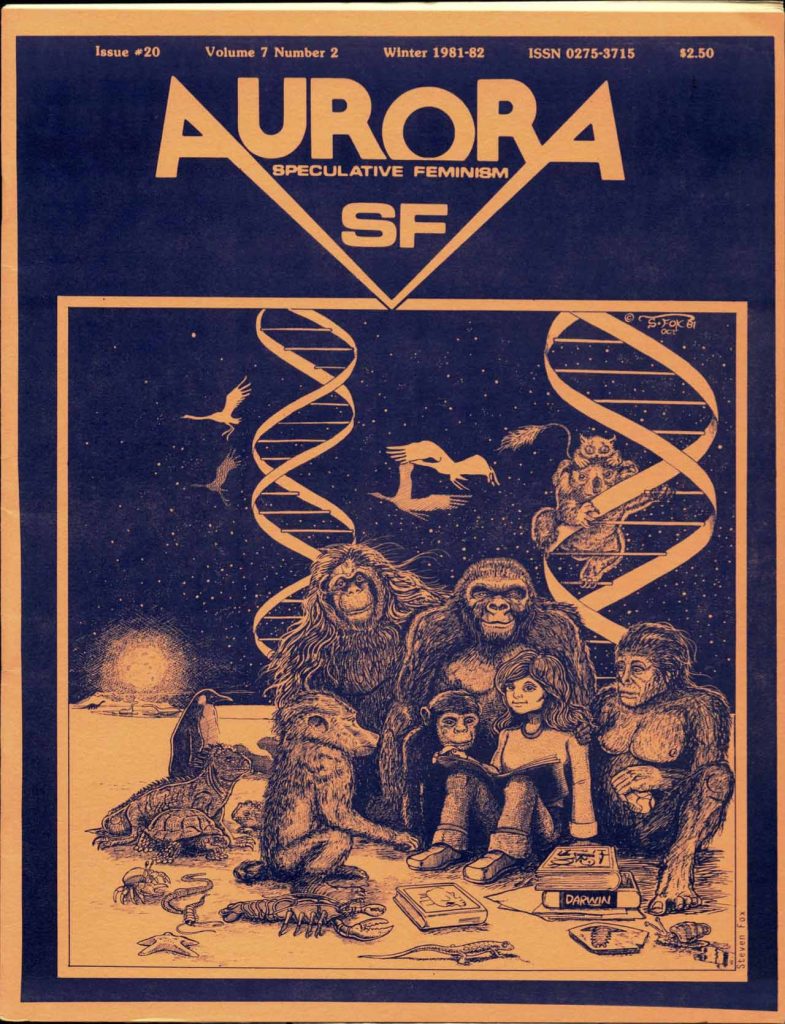

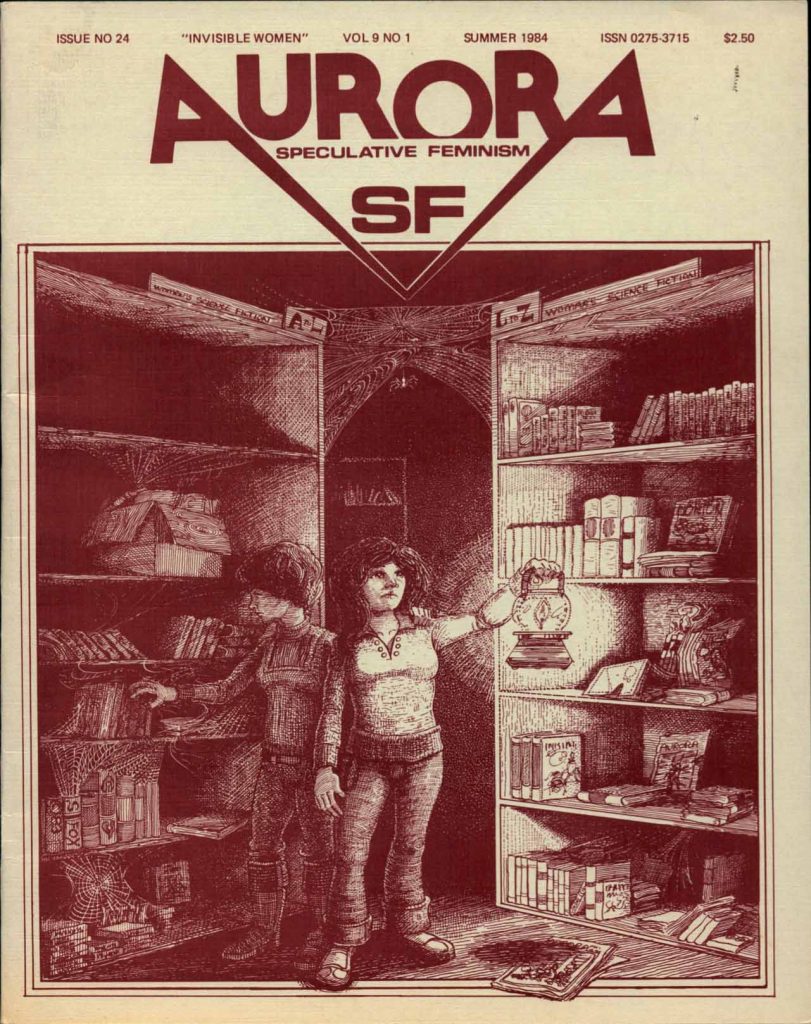

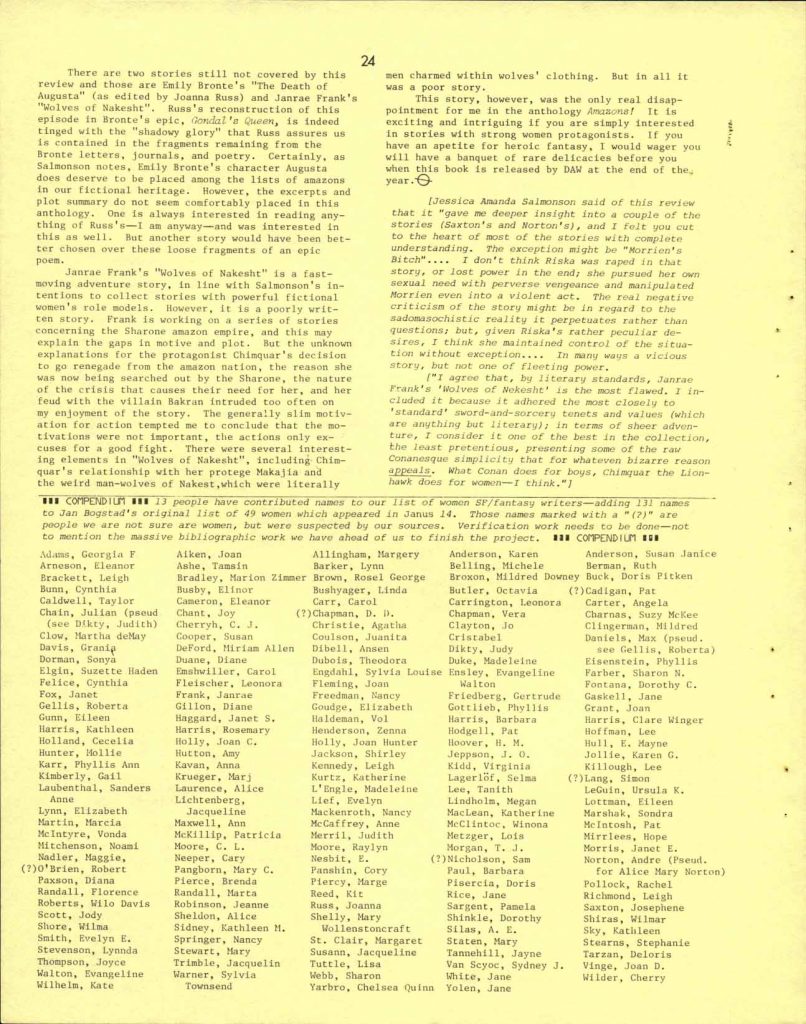

In 1975, a SF fan by the name of Janice Bogstad created a feminist SF fanzine called Janus, that was later printed under the title Aurora, based in Madison, Wisconsin. By the sixth issue Bogstad had invited Janus/Aurora’s main contributing artist Jeanne Gomoll to become co-editor.3 Issues were dense with content for the fandom to enjoy, at times running up to fifty or sixty pages. For such a concentratedly feminist SF fanzine, Janus/Aurora supplied high quality columns, SF stories, artwork, debates, and much more to its fans. They succeeded in producing, publishing, and distributing 26 issues altogether between 1975 and 1990. Contributors and fans of this fanzine included both men and women, which was beneficial to a variety of dialogues concerning gender, sex, and sexuality at the time. Janus/Aurora is remarkable in its depth of feminist issues and SF interests, connecting women fans who felt alienated, as well as its dedication to the women of SF fandom who were often not well-represented in mainstream speculative fiction works or fandom.

Temporality in Janus/Aurora

Janus/Aurora looks to SF’s relationship to the past, present, and future as a way to understand the temporality of feminist science fiction and imagine possible futures for women. SF has often fallen prey to misogyny, sexism, and the overall misrepresentation or erasure of women characters and writers.4 In the eyes of feminist SF fans there are uses and possibilities of the SF genre for a better tomorrow that includes women. In Issue #5 of Janus, Bogstad writes an article entitled “The Future of Future Histories” that details the concept of future histories5 in SF literature, although not a concept she developed herself.6 She describes future histories as, “a fictional scheme, encompassing a broad timespan, set in a future time.”7 When authors write these fictional schemes they are essentially planting little seeds in the reader’s mind to envision a new future that is different from the future we see ahead in the real world. To contemplate future histories in SF is to allow ourselves the creativity and freedom to look for an alternative to the structures and inequalities that constrain us in the present moment. Bogstad refers to the works of Ursula K. Le Guin, Marion Zimmer Bradley, and Katherine Kurtz as examples of women SF writers who have constructed future histories. Bogstad states, “A Future History is not simply a series of books about one subject but rather a system for the future which operates as if it were a known past. It is a history of the future.”8 The creative expression used to develop future histories is stimulating for readers because it shows them that not everything is fixed, but rather a construction or possibility.

Issue #5 of Janus also contains a film review by Philip Kaveny of Logan’s Run (Michael Anderson, 1976), which was adapted from a novel by the same name written by William F. Nolan and Clayton Johnson, that discusses the future and present.9 Logan’s Run follows a man named Logan living in a future utopian society where everyone is beautiful and lives well, although this utopia comes at the price of each member of society being sent to death by the age of 30. Kaveny finds that the future history found in Logan’s Run offers an allegory for how we presently live. He wrote this review in the 70’s, but strangely enough in 2018 we can presently look to a past interpretation of a future history and still feel its relevance. Kaveny says, “We live in a world that seeks to hide and perhaps denies all that does not conform to the ideals as presented in so much of our media of youth and beauty. That which is unique and does not conform is hidden or perhaps institutionally murdered.”10 Conformity, youth, and beauty are essential characteristics of American society. Kaveny views the temporality in Logan’s Run as a future history that is essentially an extreme version of our present values as a society. The film offers an example of the type of future history we should avoid in creating as we move forward for human and technological advancement.

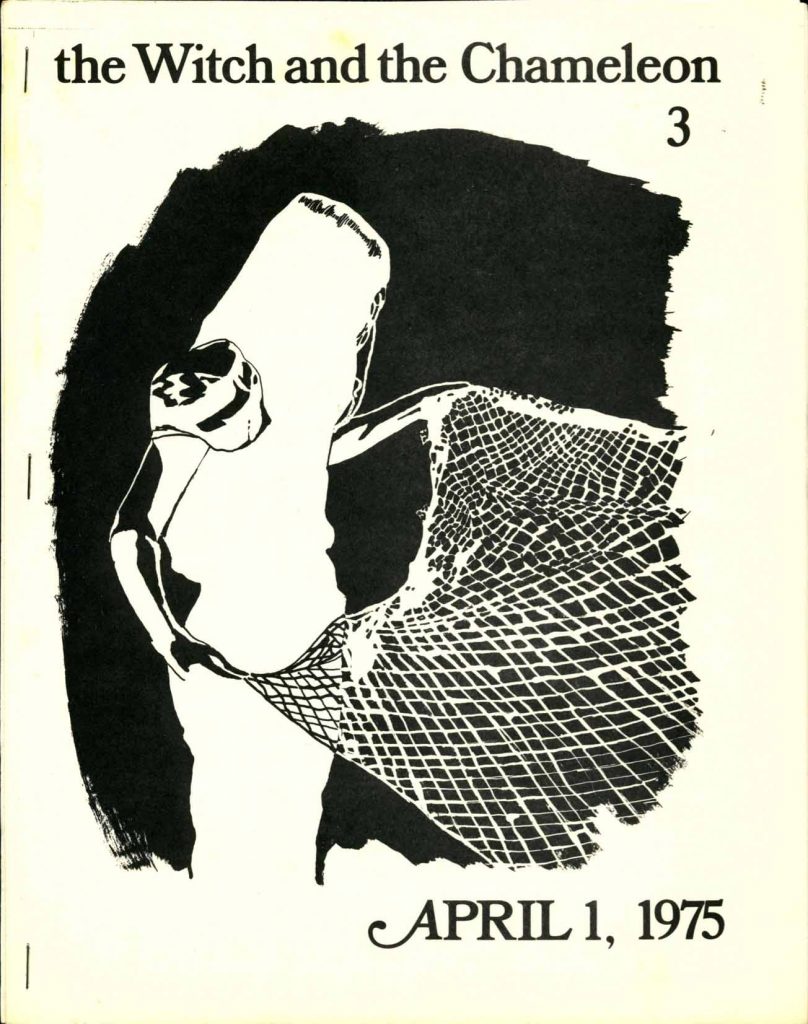

Amanda Bankier and The Witch and the Chameleon

Before the production of Janus/Aurora there was the first feminist SF fanzine The Witch and the Chameleon created by Amanda Bankier, which is also considered to be the first explicitly feminist fanzine.11 Acknowledging Bankier’s place in the history of feminist SF is precisely the type of recognition that Janus/Aurora worked to do within their own fanzine. Bankier’s fanzine was short-lived, running from 1974 to 1976 with only 5 issues and one issue being a double-issue, but had a huge impact on Janus/Aurora and other feminist SF fans. Bankier created The Witch and the Chameleon as a way for women SF fans to talk with each other, using feminism as a political framework to push for the inclusion of women as writers, characters, and fans in the overall SF fandom. Bankier invited contributors to write for her fanzine including writers and artists such as Vonda N. McIntyre, Jeanne Gomoll, Suzy McKee Charnas, Joanna Russ; all of whom had contributed to Janus/Aurora. The Witch and the Chameleon featured editorials, stories, poetry, artwork, political talk and analysis on speculative fiction, much like Janus/Aurora.

Bankier’s work was recognized early on in Janus/Aurora, with Bankier’s first appearance in the #4 issue of Janus with a letter she sent commenting on famed SF writer Andre Alice Norton.12 By issue #6 there as an announcement that Amanda Bankier would be the Fan Guest of Honor at WisCon, alongside Katherine MacLean as Guest of Honor.13 The #4 issue of Janus also included a section entitled “Lunch and Talk” that featured a transcription of a conversation between Janice Bogstad, Jeanne Gomoll, Amanda Bankier, and Suzy McKee Charnas14; a talk that is recognized later in Janus as the article that’s received more feedback than anything else that had been printed to that date.15 The endearing element of Amanda Bankier’s relationship to Janus/Aurora is that the latter recognized Bankier’s prominence in fandom, making sure to celebrate and include her with the happenings of Bogstad and Gomoll’s fanzine. Janus/Aurora had a much longer and extensive run as a feminist SF fanzine than The Witch and the Chameleon, but Bankier’s fanzine sparked the drive amongst women in the SF fandom to network more amongst each other through the fanzine medium.

WisCon

One of the monumental feats of Janus/Aurora was their construction of WisCon, the first ever feminist SF convention. Not only was the fanzine heavily interactive, but WisCon translated that involvement to face-to-face encounters during an annual weekend gathering. As the name denotes, WisCon is held every year in Madison, Wisconsin, with it’s 43rd run occurring in 2019 (www.wiscon.net). It came into discussion over meetings of MadSTF which was a local SF club in Madison, Wisconsin that got together to plan fan activities, play Dungeons & Dragons, and debate speculative fiction. The first WisCon occurred in February of 1977 and was sponsored by the Society for the Furtherance and Study of Fantasy and Science Fiction, also known as SF3, which is a non-profit organization that supports fan activities and is closely linked to Janus/Aurora.16 Issues #7 and #11 of Janus are considered program books about the upcoming WisCon events for the first two conventions.1718 After WisCon there would be “Con Reports” that shared the experiences, thoughts, approvals or problems that contributors and fans had about the convention. Janus/Aurora contributors and fans also reported on their attendance of other well-known conventions such as WorldCon, MidAmeriCon, IguanaCon, Noreascon, Chicon. However, WisCon was a decidedly new kind of SF convention that gave attention to women, feminism, and speculative fiction. It provided a platform for areas of interests to women in the fandom who often could not make their voice heard. WisCon has become a highly regarded convention that promotes the discussion, learning, and understanding of issues regarding the intersectionalities of gender, race, and class, both in and outside speculative fiction.

Janus issue #11 is the program book for the upcoming WisCon 2 of 1978, with articles by and about the Guests of Honor Susan Wood and Vonda M. McIntyre.19 After the test run of the first WisCon of 1977, this second program lays out more decisive plans for WisCon 2 that were assembled around recommendations resulting from the first convention. The second program book describes the plans to have three public access rooms at WisCon 2; each room dedicated to mini-events, panels, discussions, readings, presentations, screenings, artistic demonstrations, and games.20 Some of the event titles included: “Fascism & Science Fiction Workshop,” “Children’s Role Models in Juvenile Science Fiction,” “Women’s APA Suite,” “Feminism: To Grasp the Power to Name Ourselves, Science Fiction: To Grasp the Power to Name Our Future,” “Sex and Gender in Science Fiction,” and “Women in Fandom.”21 As seen by these titles there were an array of considerations and interests to the fans attending WisCon. The articles provided by Susan Wood and Vonda M. McIntyre, as well as the contributors who provided their own biographies of the respective Guest of Honors, underlines one of the major motivations for WisCon which is to honor women SF writers and their personal interests. Famed SF author Ursula K. LeGuin composed a bibliography and tribute to Vonda N. McIntyre’s work, presenting an example of women supporting women in SF fandom.22 Wood’s guest editorial entitled “People’s Programming” explores her relationship to fandom, being a woman in fandom, the women’s movement, and criticism of the sexism and misogyny within fandom.23

Applying Feminist SF to Academic Studies

Janus/Aurora saw feminist SF as something that could be useful in pedagogical methods related to academia and different areas of study. Feminist SF came during a period of consciousness raising24 in the women’s movement. This period of feminism inspired women to find ways to share and apply their newly found knowledge about different intersectionalities of gender, race, sex, sexuality, and class.

Many issues of Janus/Aurora were formulated around different themes. Issue #23 of Aurora’s 1983-84 winter edition focused on the theme of “Education & SF,” introducing a number of articles and columns focused on SF’s potentialities in education.25 SF author and linguist Suzette Haden Elgin contributed an article discussing her construction of a language for women called Láadan that is used to disrupt male-centered language.26 Learning Láadan would be beneficial to students and fandom in order to broaden their concepts of language and question patriarchy. Elgin says, “ Now, when women are asked why no women ever made up a woman’s language, they can say: ‘As a matter of fact, there is one example of such a language on record…’ and so on.”27 This becomes relevant to a later column included in Issue #23 written by Barbara Emrys entitled “Teaching SF as Women’s Studies.”28 Emrys considers SF as a chance to reveal to young students taking women’s studies courses a variety of stories and images of strong women characters. One could liken the teachings of SF across different areas of studies to the teaching of critical thinking across majors. SF opens the mind and offers alternative ways of thinking that provide potential futures for students.

Media theory is touched upon in Janus/Aurora and becomes applicable to feminist SF and education. The consumption of different SF media is met by analyzation and critique of fans, thus becoming a kin to media studies. After attending a convention, Bogstad came back to report on her thoughts about mass media and culture.29 She refers to the Frankfurt school30 and the distinctions made between high, mass and popular culture. SF fandom to her understanding finds its place in popular culture. Bogstad says, “What is popular culture? It is not the books or comics that are published, the old or new movies, toys of past eras. Rather it is activity and human interaction – the activity of fandom for example.”31

She also draws upon this conclusion because of fandom’s role as both producers and consumers of their own culture. Bogstad’s comments ring true in Phil Kaveny’s reports in the same column about media and culture. Kaveny says, “We are all interested in popular culture as an alternative to mass culture.”32 He finds public-access and community radio as helpful tools in supporting the producer and consumer roles found in fandom.33 Kaveny describes a once-a-month public access show featuring a Dungeons and Dragons game that encourages viewers at home to call in and direct the game as a compelling use of different media. The 70’s and 80’s in which Janus/Aurora was produced becomes an integral point in time to be studied and understood in the ways of media studies.

Creating a Better Tomorrow

The Janus/Aurora feminist SF fanzine was created out of the convictions and motivations of women in fandom who wanted to create change in their community. They saw the freedoms that were opening up during the radical 60’s and chose to run with other counterculture groups in fighting for something meaningful. Janus/Aurora used its platform as a way to uplift and represent women SF authors, artists, fans, and many more. Janice Bogstad chose to take action and foster a space that women fans could speak freely about their interests and opinions without the feeling that someone might come and shut them down. Not only did Janus/Aurora nurture the fandom’s discussion of speculative fiction, but it kept fans involved in political concerns within American society. Janus/Aurora was a collaborative, participatory, and interactive effort that represents the authenticity of SF fanzines and fandom.

- “Speculative fiction.” Wikipedia, 13 June 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speculative_fiction. Speculative Fiction is an umbrella genre encompassing narrative fiction with supernatural or futuristic elements. ↩︎

- “New Wave science fiction.” Wikipedia, 1 April 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Wave_science_fiction. The New Wave movement in science fiction occurred during the 1960’s and 70’s and characterized by high degrees of experimentation in form and content; focused on “soft” science instead of hard. ↩︎

- Janus, Vo. 2, No. 4. (Madison: SF3, 1976), 2. ↩︎

- Joanna Russ, How to Suppress Women’s Writing (Austin: University of Texas, 1983). ↩︎

- “Future history.” Wikipedia, 28 May 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Future_history. Future history is used by SF and speculative fiction authors to postulate a history of the future; coined by John W. Campbell, Jr. in the Astounding Science Fiction magazine in 1941. ↩︎

- Janus, Vo. 2, No. 3. (Madison: SF3, 1976), 4-5, 16. ↩︎

- Ibid, 4. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid, 38-39. ↩︎

- Ibid, 39. ↩︎

- “The Witch and the Chameleon.” Fanlore, 9 May 2018, https://fanlore.org/wiki/The_Witch_and_the_Chameleon. ↩︎

- Janus, Vo. 2, No. 2. (Madison: SF3, 1976), 9.

↩︎ - Ibid, 2. ↩︎

- Ibid, 23-28. ↩︎

- Janus, Vo. 3, No. 2. (Madison: SF3, 1977), 30. ↩︎

- Janus, Vo. 6, No. 2. (Madison: SF3, 1980), 29. ↩︎

- Janus, Vo. 3, No. 1. (Madison: SF3, 1977). ↩︎

- Janus, Vo. 4, No. 1. (Madison: SF3, 1978). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid, 14-15. ↩︎

- Ibid, 16-21. ↩︎

- Ibid, 9-10. ↩︎

- Ibid, 4. ↩︎

- “Feminist Consciousness-Raising.” National Women’s Liberation, 2018. http://www.womensliberation.org/priorities/feminist-consciousness-raising. Consciousness raising is a tool used by the Women’s Liberation movement that was adopted from the Civil Rights Movement in the 60’s in order to understand the political root of their oppression. ↩︎

- Janus, Vo. 8, No. 3. (Madison: SF3, 1983). ↩︎

- Ibid, 10. ↩︎

- Ibid, 12. ↩︎

- Ibid, 26. ↩︎

- Janus, Vo. 5, No. 2. (Madison: SF3, 1979), 29. ↩︎

- “The Frankfurt School and Critical Theory.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, n.d. https://www.iep.utm.edu/frankfur/. Frankfurt School was founded in 1923 as a philosophical and sociological movement that helped develop critical theory; often critiquing culture, capitalism, media, and society. ↩︎

- Ibid, 30. ↩︎

- Ibid, 29. ↩︎

- Ibid, 30. ↩︎