Belief in witchcraft, magic, and sorcery has been prevalent throughout history and practiced all over the world: in ancient Mesopotamia, the Middle East, Africa, the Americas, Europe, Oceania, and all through the Asian continent. Each culture and region hold different beliefs and attitudes toward these practices. While there are both helpful and harmful forms of magic stemming from regional folklore, in America we tend to associate witchcraft with pagan ritual and heretical malevolence against Christianity. This is largely due to early European influence, the paranoia and efforts of those associated with the Catholic and Protestant church, and through the sheer volume of their writing and admonition of the subject during the medieval and colonial periods. Accordingly, any belief or practice outside those deemed acceptable by the social and cultural standards were subject to scrutiny. And accusations of sorcery and witchcraft (specifically toward commonfolk) had dire consequences.

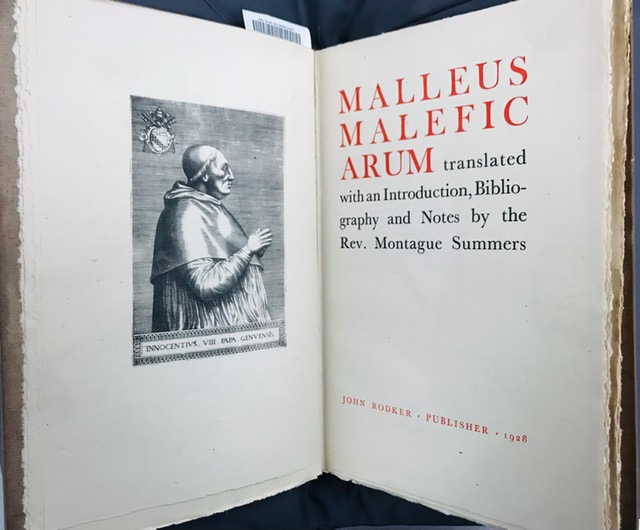

The Malleus Maleficarum, written in 1486, is one of the first texts ever published on the subject of witchcraft. Written by two German theology scholars and members of the Dominican order, the work set out to prove the existence of witches as heretics and acted as a manual to rid them from society through trials, torture, and brutal deaths. The Malleus Maleficarum, which translates to “Hammer of Witches,” was instrumental for creating nearly three centuries of witch-hunting hysteria throughout Europe and North America.

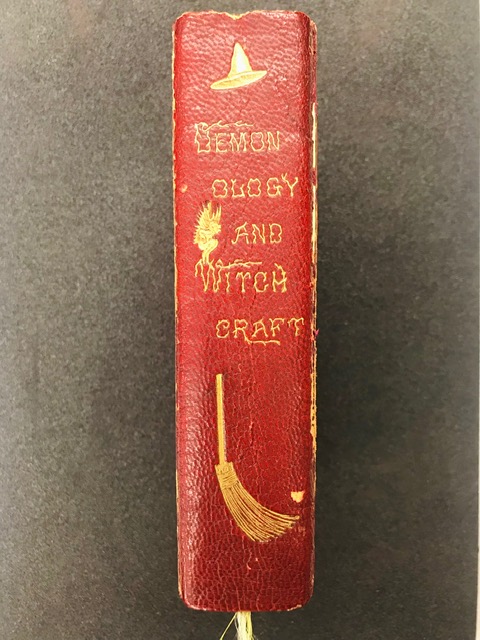

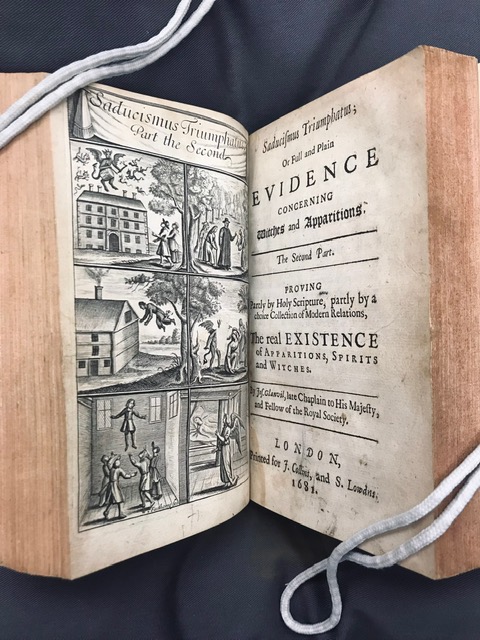

It was the belief that witches, most commonly associated with women, had pacts with the Devil to undermine the virtue of Christianity or disrupt the natural world. Witches rode atop animals during the night to hold meetings with Satan, fornicated with demons, caused crop failures, killed children and prevented married couples from conceiving through spells, among other heresies. This interaction between women, Satan, and clandestine activity was paramount in the Christian European mindset toward witchcraft, especially during the Reformation.

Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584) was written nearly 100 years after the Malleus Maleficarum. Scot was the first English writer to expound upon the subject of witchcraft and he intended to disprove the theory that witches contained real supernatural powers, but were instead resourceful women who practiced the art of folk healing. Scot rejected the idea that Satan or any supernatural being could interact with humans, and that the charms of witchcraft, or indeed even the rites of Catholicism, were merely superstitious. Because of these beliefs, Scot’s contemporaries condemned him as impious. Even King James VI rebutted Scot’s theory with his own Daemonologie, which focused largely on necromancy and doubled down on the threat witches posed. It was rumored that James had ordered every copy of Scot’s book to be destroyed, but there is no evidence to support this. However, after the first edition, The Discoverie of Witchcraft was not published again in England for nearly 70 years.

During the period after Scot’s death, the thesis he set out to prove as a testament to reason and critical thought took on a perhaps cursed irony. The magic and sleight of hand Scot tried to uncover were seized upon by his more esoteric successors and spread into popular culture, cementing their place into witchcraft ethos. Even Shakespeare was likely to have been influenced by Scot when writing Macbeth.

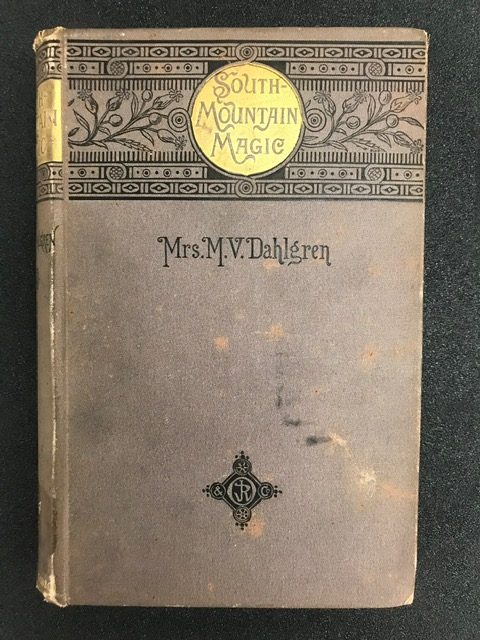

Well after the hysteria of the witch-trials had ended in Europe and America, rural traditions held on to the superstitions and beliefs of the occult. Madeleine Vinton Dahlgren’s South Mountain Magic, published in 1882, described the folklore of ghosts, witches, and demons of South Mountain, located near Boonsboro, Maryland. She described local lore such as the Snarly Yow (a giant demon-like dog), haunting apparitions, as well as magic cures for common ailments.

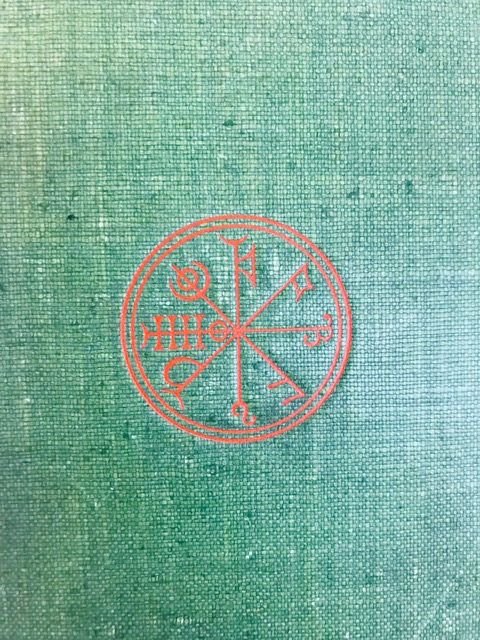

The mid-twentieth century brought about newfound interest in the occult through neopagan groups like Wicca, Anton LaVey’s Church of Satan, and a proliferation of authors and film directors that showcased, and often exploited, these ideas through new mediums. Today we have a better understanding of how these “superstitions” and social accusations originated that were tragically cast upon women (and men as well). So, as Samhain approaches and we celebrate the year’s harvest and the changing of the Hunter’s Moon, feel free to light some candles, open an old book, and conjure the spirits of our historical past.

View these titles and more by request in our reading room. This post was written by Mark Breeding, Maryland Traditions Archivist.