When someone asks me to explain my job, my go-to answer is that I work in a book warehouse. Admittedly, it is flawed as explanations go. First, the book part is not strictly accurate. The department’s holdings are far more eclectic than just old books. Photographs, fanzines, old pamphlets, newspapers, and papers from scientific associations are a few examples of the items I work with. Second, the labor involved varies beyond the purely physical. Though much of my job involves moving, storing, and organizing objects, it also requires non-physically intensive duties like data entry, office work, and writing blog posts.

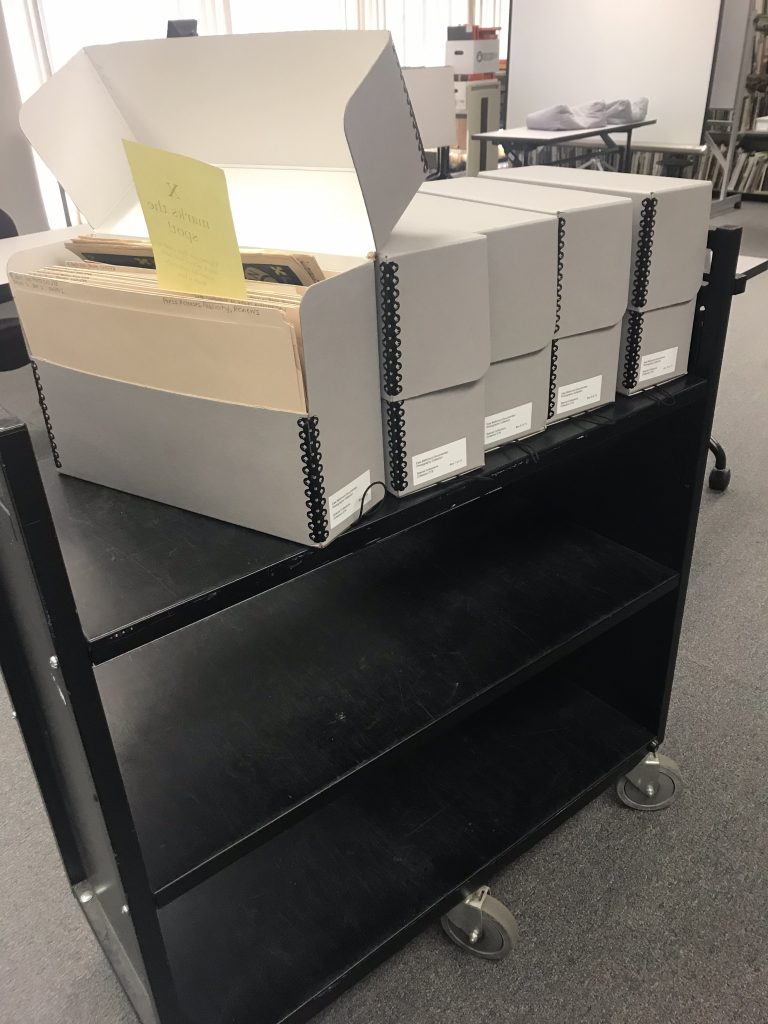

So why do I always start with physical labor when explaining my job? There are two reasons. First, it surprises people. Truthfully, it surprised me too when I started working here. When people think about archives, they do not think of physical labor. Archivists are professionals; people who work with their brains rather than their hands. Yet I worked with my hands just as much—if not more—than I talked to our researchers. Indeed, the customer service aspects of the job directly relate to physical labor. Researchers come to our reading room to read something, something that needs to be found, retrieved, and prepared for public consumption. Second, I enjoy physical labor more than any of my other duties. There is something satisfying about tracking down a single item in a sea of others, filling up a cart with all the items needed for a class, or reorganizing a shelf so that a new edition can fit in its proper location.

The importance of physical labor in archival work raises essential questions about keeping the job accessible. Since 2010, the profession has strongly pushed to ensure the rights of archivists with disabilities. The Society of American Archivists (hereafter the Society)—the leading professional association for archivists in the United States—published a series of guidelines to make the archives an accessible workplace. The Society recommended reforms to the hiring process, building space, and employee policy to prevent discrimination against people with disabilities. Though these guidelines are certainly a step in the right direction, two significant factors limit the full implementation of these reforms: space and technology.

Regarding space, Special Collections only has limited rooms available to store items. This means that certain storage areas are narrow, particularly in one room. This would likely make it difficult for someone in a wheelchair to navigate. Compounding this is the older nature of the technology we use to retrieve and store items: hand cranks to move certain shelves, slightly rickety step stools to retrieve objects on higher shelves, and push carts to move items across the complex. These tools are hardly the most accessible for archivists with physical disabilities. Given the financial resources of the archive and the university, these are the resources we need to work with.

As someone with a diagnosed disability, I have some firsthand experiences with the frustrations that sometimes come up on the job. One of the stronger parts of being autistic is never quite knowing where I am in space. The way I like to explain it is that everything I see is tilted at a 25-degree angle. So, everything always seems either closer or further away than it is. This spatial distortion is problematic when trying to ensure I do not crash a loading cart into the main room door. Likewise, physical writing is difficult for me. Even something as simple as filling out a series of call slips to mark an item’s location can become painful. That said, I have no plans to change my duties at Special Collections. These tasks are essential for the archive’s functioning, and I enjoy them. However, the ability to power through a disability is a privilege not everyone possesses. Thus, UMBC Special Collections must continue to do all it can to ensure that the work remains accessible to every potential archivist, student worker, and volunteer.

This post was written by Yoni Isaacs, ’22, history, M.A. ’26, history, a graduate assistant in Special Collections. Thank you, Yoni!