When UMBC began its first semester in 1966, the initial 750 students and 45 faculty members came to campus and established an atmosphere of diversity and open dialog. Members of the community were committing to their academic pursuits in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement and soon after, the Vietnam war, a truly turbulent time in American society outfitted with instances of campus unrest. Students started asking questions and demanding answers across college campuses in order to enhance their collegiate experience and change their campus environment. An instance of asking questions and demanding answers came in the late 1960s, when students began to ask why there hadn’t been an established, degree-granting African American Studies Department, supported by African American cultural studies and literary scholars and professors. Higher educational institutions started to embrace the intellectual validity of cultural studies and neighboring institutions had already begun work to build programs to support this growing interest for students. And so, with the approval of the Maryland Council for Higher Education (MCHE) in 1972, the new department was solidified in UMBC’s curriculum.

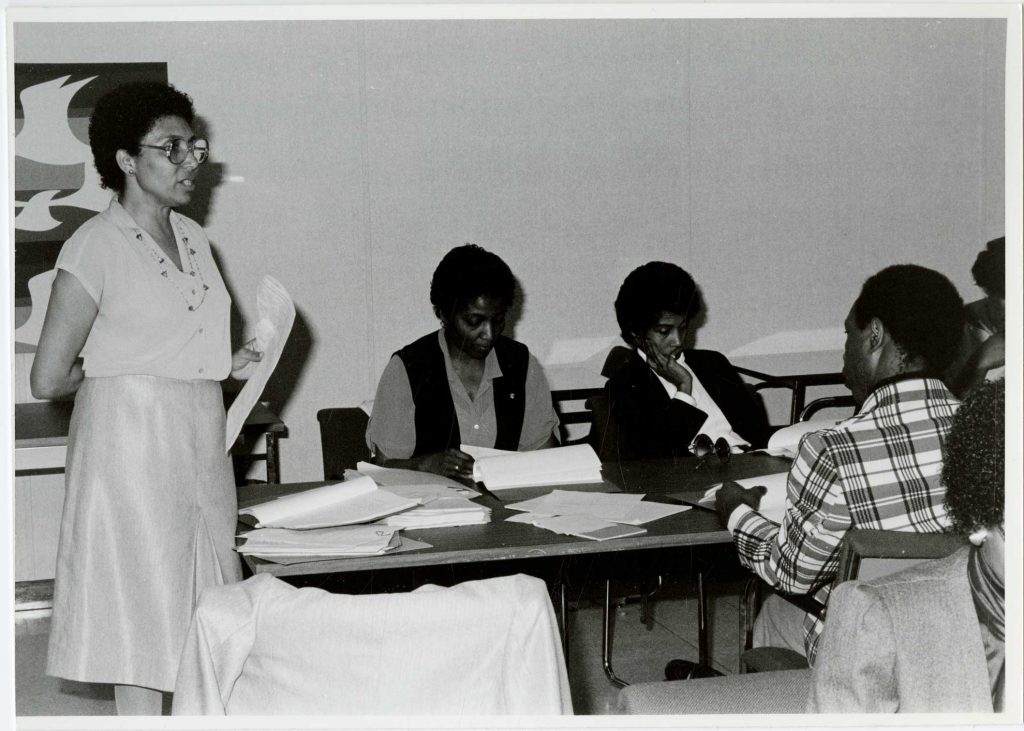

The African American Studies Department planning committee in 1973 included Dr. Daphne Harrison, who initially served as the Acting Director for the program, and fully reassumed the position from 1981-1992. Through her work and the inaugural faculty and staff, the curriculum explored areas of the African diaspora in Africa, North America, and the Caribbean. The W.E.B. Dubois Distinguished Lecture series was established, and interdisciplinary connections became more solidified across departments.

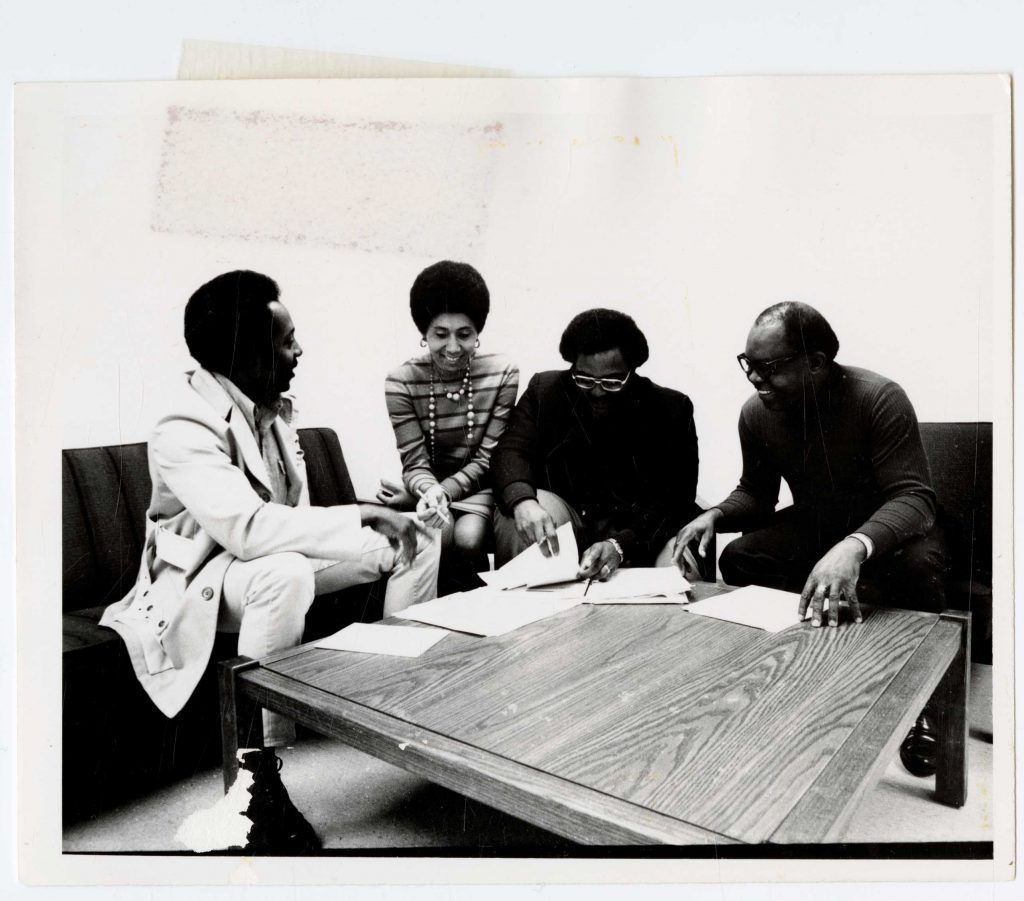

William E. “Skip” Boyd, [Africana Studies faculty and staff], circa 1970s. Gelatin silver print, 4 x 5 in. University Archives, UARCPhotos-08-0012.

However, the Africana Studies records not only provide a spotlight on the development of the department, it sheds a light on the temperature on campus from its beginnings. In order to develop a program of integrity and substance on campus, faculty members and administrators involved in the department’s establishment thought it necessary to investigate the perspectives, biases, and relationships on campus that could better inform them of what the actual experiences of black students, staff, and faculty on campus were like. A series of efforts through surveys, interviews, and written testimonials, all captured in the collection, lends deep insight into what interactions and relationships looked like within what was then still a predominantly white population. The National Institute of Health’s Racism Intervention Development Program here at UMBC directly tackled the lack of awareness of, and developed solutions for issues that faced minority students at predominantly white institutions. This program brought a high level of exposure to understanding institutional racism in higher education, along with other participating institutions who were prepared to question and address this issue during the mid-1970s. It also took a direct look at opportunities of intersectionality across already established departments.

The collection also features reference documentation, correspondence, and proposals associated with the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute for Teachers, a grant-funded program specifically targeting high school teachers, to enhance their teaching approaches on African American studies teaching of history, culture and literature. Not only did UMBC’s African American Studies program build itself, it also promoted its growing expertise by creating opportunities to expand the reach of exposure to African American studies curriculum.

Post by Laurainne Ojo-Ohikuare, Processing Archivist