It should come as no surprise that the period of Reconstruction after the Civil War remains one of the most complicated times in American history. Three separate amendments were added to the constitution, three civil rights acts were passed (although one was later deemed unconstitutional), and innumerable pieces of legislation made their way into committee. These laws primarily served two purposes: firstly, to free enslaved peoples and provide for them assistance, and secondly, to ease tensions between the North and South. One of the most important legislative acts during Reconstruction was the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, which established a governmental agency within the United States Army to serve as a relief system for formerly enslaved peoples under the thirteenth amendment. The Bureau were to provide clothes, shelter, and supplies to formerly enslaved peoples and to protect them from Southern whites who sought to keep them extrajudicially.

Another key role of the Bureau was that of education. As enslaved peoples were not allowed formal education, it was essential that, once freed, they had access to some form of learning. Without education, African Americans in the South had no way to develop new trades and skills, and were far more vulnerable to violations of their rights. Teachers from the North volunteered through organizations such as the National Freedman’s Relief Association, Gloucester Freedmen’s Aid Society, and numerous religious-based organizations, to move to the South and operate schools for formerly enslaved peoples, known as Freedmen’s schools.

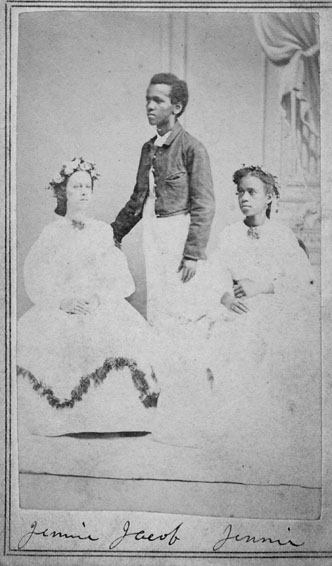

Funding for these schools proved a much greater challenge than founding them, however, and nationwide fundraising efforts were established, to varying degrees of effectiveness. One of the most effective means, however, is represented by photographs in the Ronald Rooks Collection, housed in UMBC’s Special Collections. Under direction of the National Freedman’s Relief Association, dozens of photographs of formerly enslaved peoples, especially children, along with their teachers, were made and distributed for sale as cartes de visite across the northern United States with the proceeds supporting the Freedmen’s schools.

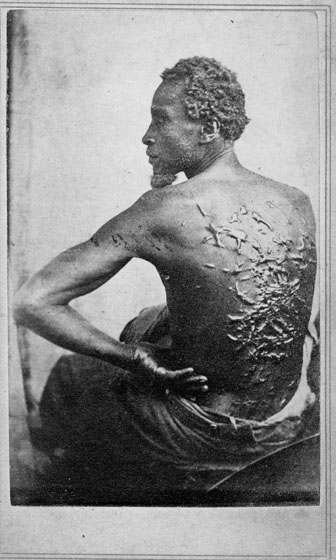

A carte de visite is a small photographic print on a paper mount, designed for a large quantity of production. They were inexpensive and didn’t require any sort of special viewing device, and so they proved incredibly popular during the Civil War and early Reconstruction. They functioned not unlike a calling card or trading card, and so they quickly became a very powerful means of propaganda. Photographs of politicians and celebrities could be distributed widely as cartes de visite, and abolitionists such as Sojourner Truth also used them to fundraise and to spread messages about the horrors of slavery. One of the most important images of the time was that of Gordon, who escaped enslavement and allowed his back to be photographed, showing the extensive scarring from whippings endured from slave owners. This image became infamous when it was distributed as a carte de visite and reproduced in the illustrated news magazine Harper’s Weekly. Printed on the verso of the carte de visite was Gordon’s story, which confronted Northern viewers with the true barbarity of his treatment. Pro-slavery propaganda had convinced many Northerners that enslaved peoples were only mistreated if they were disobedient, but Gordon’s story proved that to be a lie. The image and accompanying text proved to be a powerfully persuasive tool in the abolitionist movement, garnering support for the Union Army’s cause.

Some of the cartes de visite sold in support of the Freedmen’s schools were intended to draw sympathy from philanthropic Northern whites, and none proved more effective than those depicting the so-called white slaves. These were children who were born into slavery, but who appeared to be white. Much of the popularity of these images stemmed from Northern fears that should slavery continue unabated, whites would soon become enslaved alongside blacks. As noted by historian Mary Niall Michell, “their images appealed to Victorian sentiments about white rather than black or ‘colored’ girlhood.” Nonetheless, these images provided an immense amount of fundraising for the schools for Freedmen.

Art as propaganda has existed for millennia, but photography and mass production took things to a new level, as clearly demonstrated by the carte de visites of Reconstruction-era America. It is impertinent to say that they single-handedly changed the hearts and minds of northerners, but it is also undeniable that they had an impact on our history.

Post by Ben Rybczynski, former Special Collections intern and Gallery Assistant, written Fall 2020.

Bibliography

Mitchell, Mary Niall. “‘Rosebloom and Pure White,’ or so It Seemed” American Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Sep., 2002), pp. 369-410, accessed March 25, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/30042226

Leisenring, Richard. “Philanthropic Photographs: Fundraising during and after the Civil War” Military Images, Vol. 36, No. 2 (SPRING 2018), pp. 44-57, accessed May 28, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26348670

Parment, Robert D. “SCHOOLS FOR THE FREEDMEN”, Negro History Bulletin, Vol. 34, No. 6 (OCTOBER, 1971), pp. 128-132, accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24766513

Grigsby, Darcy Grimaldo. “Negative-Positive Truths”, Representations, Vol. 113, No. 1 (Winter 2011), pp. 16-38, accessed May 28, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/rep.2011.113.1.16