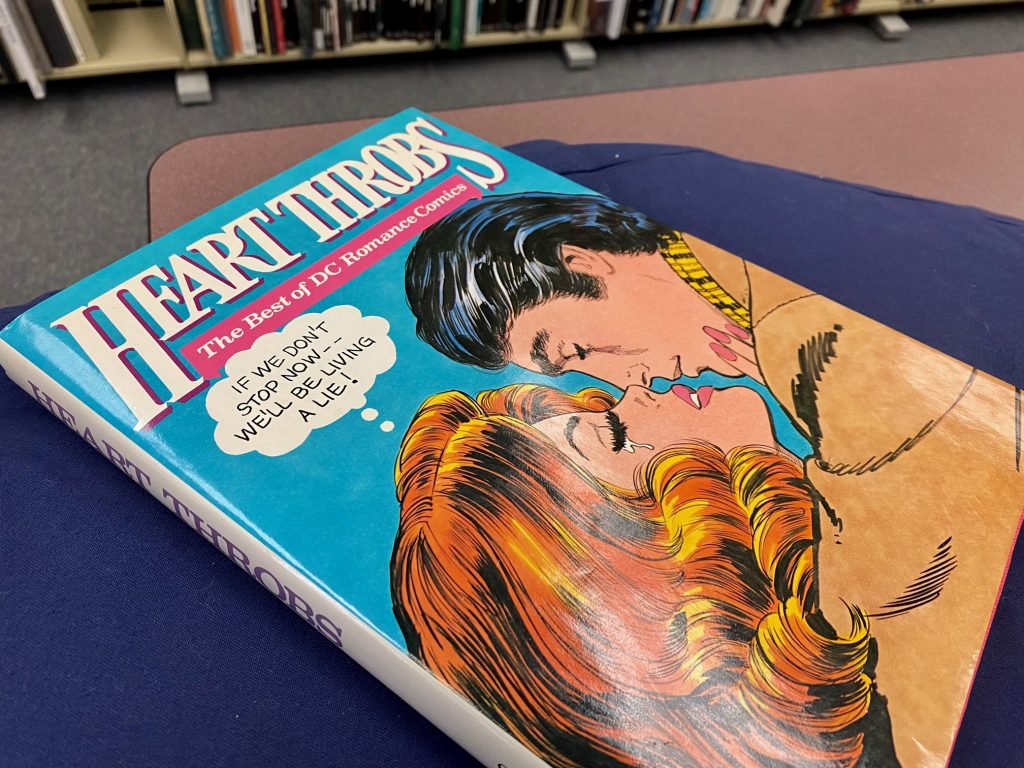

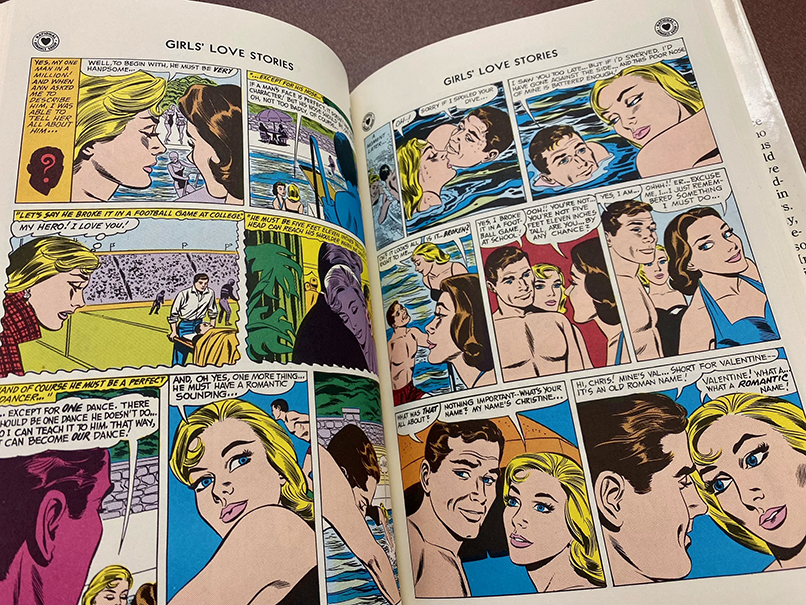

This blog post analyzes romance comic selections from Heart Throbs: The Best of DC Romance Comics (1979). The compilation book and other standalone romance comic titles can be found in Special Collections’ comic book archive, which offers an assortment of other genres such as superhero, western, horror, and more! Click here to see more information about this collection and how to access its materials.

Today’s conceptions of romance comics range from appreciation for their bright, nostalgia-evoking aesthetic appeal and dramatic flair, to derision for their cheesy, shallow nature. But at one point in time, young women and girls across America were voracious consumers of these stories, and it’s no wonder why so many were once enthralled with them. Despite the stigma attached to the romance genre, love as a motif in American media has been ubiquitous and pervasive throughout time. As love is a concept that many can relate to—or, at least, hope to relate to—romance comics offered their audience a way to secondhandedly engage with the positive and negative experiences associated with love in a highly entertaining manner. Popular media has also served as a significant vehicle through which the masses learn social scripts. For this demographic, romance comics acted as somewhat of a soft form of propaganda, as they helped express and reaffirm notions of gender and sexuality that were dominant in the given era.

While the tumultuous years of World War II saw women increasingly assume social and economic roles beyond what traditional femininity would normally allow in order to make up for the large absence of men, the postwar years called for a swift rebound back to what was considered safe, normal, and stable (that is, in the imagination of white, middle-class, heterosexual America.) After the war, American youth were transitioning into adulthood at an accelerated rate: a young woman could find herself going from being a student to a fully-fledged homemaker almost instantly! At the same time, though, came the rise of a definitive youth culture marked by rebellion that evoked anxiety within the older generations. For young women, immoral behavior was primarily defined by sexual impropriety, and the promotion of traditional values was thought to be the solution to curbing such. Romance comics mirrored this sentiment, with the heroines’ woes usually being rooted in their failure to measure up to standards of traditional femininity (ex. Disappointing her breadwinner husband by not being a proficient housewife). Though these comics could be considered progressive in the sense that they weren’t hesitant to show the heroines struggling to grapple with their newfound responsibilities and communicate how difficult these standards truly were to live up to, conflict is ultimately always resolved by the heroines miraculously finding it within themselves to conform nonetheless. Take, for example, the conflict and resolution presented in these two strips:

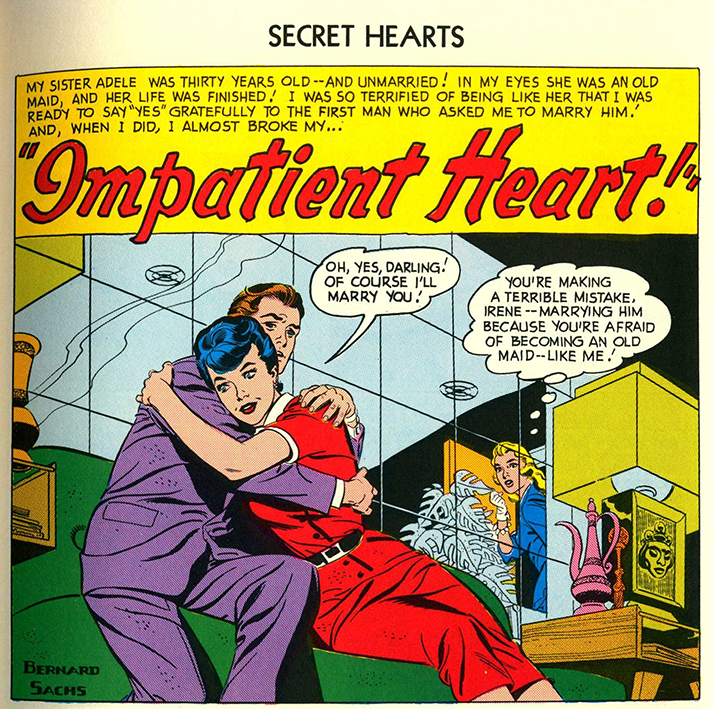

In “Impatient Heart” struggling dater Irene contemplates the prospect of marrying the first man who shows her interest lest she end up like her “old maid” unmarried sister (who, by the way, is only thirty years old…) As Irene and Dennis’s relationship progresses, she begins to have second thoughts about whether or not she truly loves him. Her apprehension is confirmed when her sister manages to find her own true love, and she notices the stark differences between their two relationships. Irene ultimately decides to call it off with Dennis, but her happiness is not achieved by overcoming the fear of being an “old maid” and finding security in being single, but rather, continuing the pursuit of finding a husband and eventually securing “the one.”

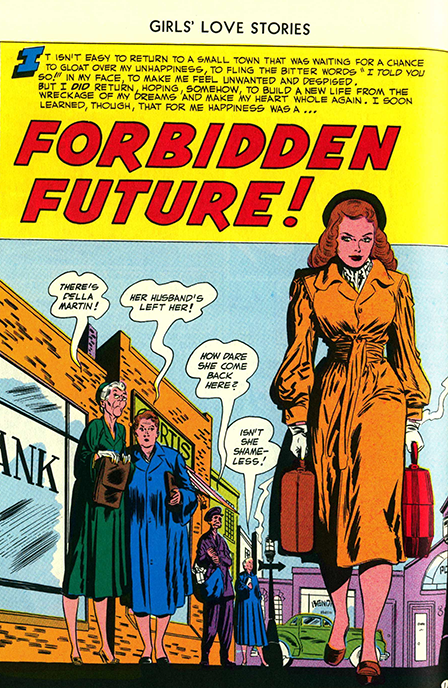

“Forbidden Future” features Della Martin, a divorcee who returns to her hometown on the receiving end of everyone’s scorn. At a social gathering, an old acquaintance named Bill Waters attempts to overstep Della’s sexual boundaries under the presumption that she is promiscuous due to her divorcee status. Handsome heartthrob Dr. Alan Marshall steps in to save her, and after getting to know each other, they quickly fall in love. However, Della is worried about damaging Alan’s goodwill in the neighborhood with her own poor image and intends to skip town, forgoing any thoughts of marrying him. On the drive out of town, Della happens to come across a school bus crash and manages to change everyone’s mind about her after she saves the children from the burning bus — a nurturing, maternal act that practically epitomizes upstanding femininity. With her womanhood restored in the eyes of the public, Della now feels confident enough to pursue a future with her newfound beau!

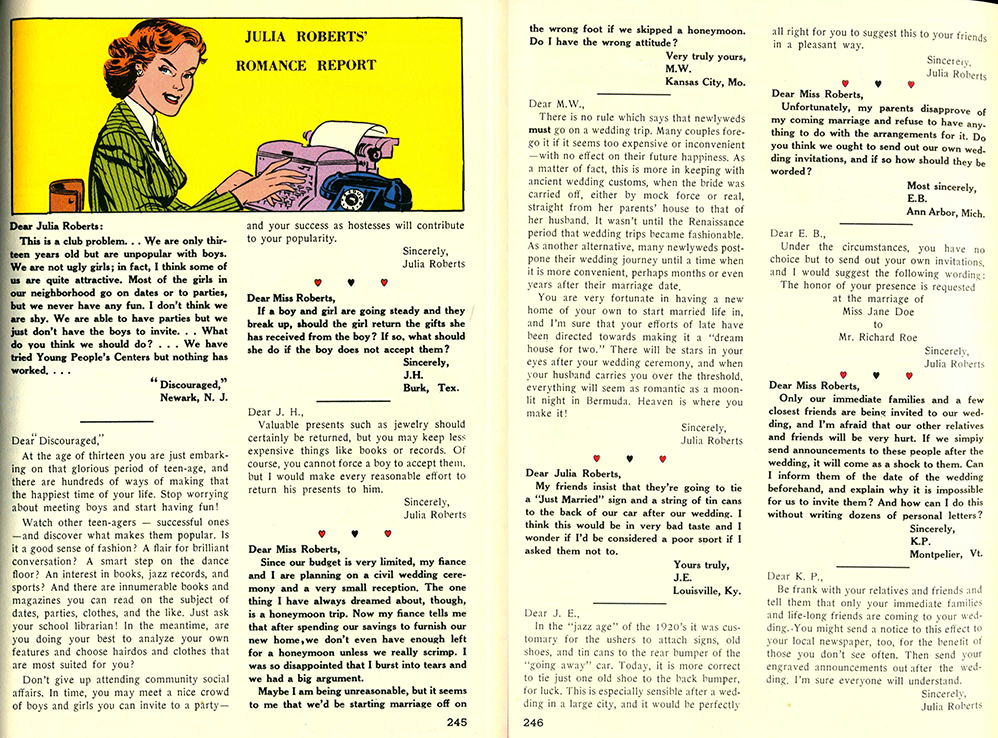

Often times, romance comics would include features aside from the strips such as self-quizzes and advice columns. If avid readers ever had a burning question on their minds, these columns existed to guide them in the right direction: “What can I do to become prettier? Do you have any tips on navigating the social scene? How do I get my dream man? Am I even the right one for him?” But while they appeared to be written by women for women, similar to the strips, they were in fact…mostly written by men. Because of this dissonance, it would be within good reason to call into question the validity of the advice provided in these columns. Fortunately for the pictured column, the man masquerading as “Julia Roberts” doesn’t provide the worst advice possible. In the first Q&A section, a thirteen year old under the alias “Discouraged” ponders why she and her friends aren’t popular with the boys in her neighborhood, and he first advises her to “stop worrying about boys and start having fun!” (though, it is a bit ironic that this is immediately followed up with advice to emulate other teens and follow beauty trends in order to improve their social standing…)

Romance comics had a relatively stable run all the way into the ’70s, but their true golden age occurred during the late ’40s to early ’50s. One simple reason for the decline in their popularity would be the combination of market oversaturation and the audience’s gravitation towards other formats such as television to consume romance media. But more salient would be the disconnect between the messages relayed in these comics and the evolving social and political ideology of its audience. While these comics would be considered incredibly tame and even regressive from a contemporary viewpoint, they drew ire from anti-comic critics who feared that the content was negatively influencing the minds of the public and encouraging delinquent tendencies. Thus, the 1954 Comics Code was enacted, which strictly censored the portrayal of any content that did not promote morality (i.e., representations of women and romance that did not adhere to conservative, patriarchal standards.) As a result, romance comics would fall out of favor because they couldn’t keep up with the ever evolving world. Their depictions of love were no longer relevant, relatable, or realistic enough for readers who were experiencing social revolutions and countercultural movements in real life. By the time restrictions were beginning to loosen and romance comics were able to incorporate more progressive and contemporary themes, the heyday of this genre had already long passed. However, even as much as we’d like to think we’ve progressed, some of the tropes and cliches present in these comics can still be seen in other popular media formats today, thereby reinforcing how deeply ingrained traditional notions of gender and sexuality truly are in our collective culture.

This post was written by Kayla Brooks, Special Collections intern currently enrolled in the historical studies graduate program.

Bibliography

Belliveau, Renée. “‘These Are Not Normal Times’: Masculinity and Femininity in Romance Pulps from the Second World War.” Journal of American Culture 44, no. 1 (January 1, 2021): 22–32.

Gardner, Jeanne Emerson. 2013. “She Got Her Man, but Could She Keep Him? Love and Marriage in American Romance Comics, 1947–1954.” The Journal of American Culture 36 (1): 16–24.

Scott, Naomi. Heart Throbs : The Best of DC Romance Comics. A Fireside Book. Simon and Schuster, 1979.

Wherry, Maryan. “Introduction: Love and Romance in American Culture.” Journal of American Culture 36, no. 1 (March 2013): 1–5.